Harald Malmgren saves the world: a fantasy set during the Cuban Missile Crisis

by Douglas Dean Johnson

@ddeanjohnson on X and BlueSky

This article was originally published on June 9, 2025. This is one of a series of articles examining certain public claims made by Harald B. Malmgren (1935-2025), with special attention to momentous events he said occurred with his personal pivotal involvement in 1962 and/or early 1963. To reach my initial foundation-laying article published on May 20, 2025, titled "Harald Malmgren: Real-world history versus grandiose fantasy," tracing Malmgren's histories – real and fictional, click here.

This subsidiary article focuses mainly on a single Malmgren claim: that in 1962, purportedly as a personal representative of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (June 9, 1916-July 6, 2009), he faced down USAF Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay (1906-1990) in a Pentagon "war room," in the presence of other top military officers, and thereby (Malmgren promoters assert) prevented a U.S.-Soviet nuclear exchange.

Any substantive additions, revisions or corrections made after the initial publication of this article will be noted in a chronological log found at the end of the article. My gmail address is my full name– first.middle.last– with periods between the names.

"You have an inventive mind. You see beyond the biggest minds." – MIT Corporation President Karl Compton, to 13-year-old Harald Malmgren in 1949, as told by Harald Malmgren in 2025

"It's rare to say this. But I think we can thank Harald Malmgren for our very existence in this world." – Christopher Sharp, editor-in-chief of Liberation Times, February 14, 2025

"In 1981, as the Historian for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, I was assigned to listen to and evaluate the classified Cuban Missile Crisis tapes in preparation for their eventual release. I heard all fifty-nine days of ExComm recordings, many other related tapes, and read hundreds of relevant documents. Harald Malmgren's name was never heard nor cited. Malmgren's claim to have been appointed as 'liaison between McNamara and McGeorge Bundy and JFK' is ludicrous. There is no such record at the JFK Library on tape or on paper." – Sheldon M. Stern, Ph.D., historian for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library from 1977 to 2000, author of three authoritative books on the Cuban Missile Crisis

"As you surmise his [Malmgren's Cuban Missile Crisis] claim is nonsense." – Sir Lawrence Freedman, Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King’s College London, eminent military and strategic historian

"Malmgren is a fantasist." – Philip D. Zelikow, J.D., Ph.D., Botha-Chan Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, co-author of The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (1997; rev. 2001)

“Falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it." – Jonathan Swift, The Examiner No. 14, November 9, 1710

Harald Malmgren's tale of how he personally stymied a push by the famous General Curtis LeMay for a punitive nuclear first-strike on the Soviet Union, during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, is worthy of close examination. In my opinion, this tale provides an excellent example of the childishly grandiose fabrications that Malmgren (1935-2025) promulgated during his later years. It may also serve as a case study in the lapses of critical judgment that allowed such a wildly improbable and ahistorical tale to be received without skepticism, applauded, and disseminated by some people who ought to have known better.

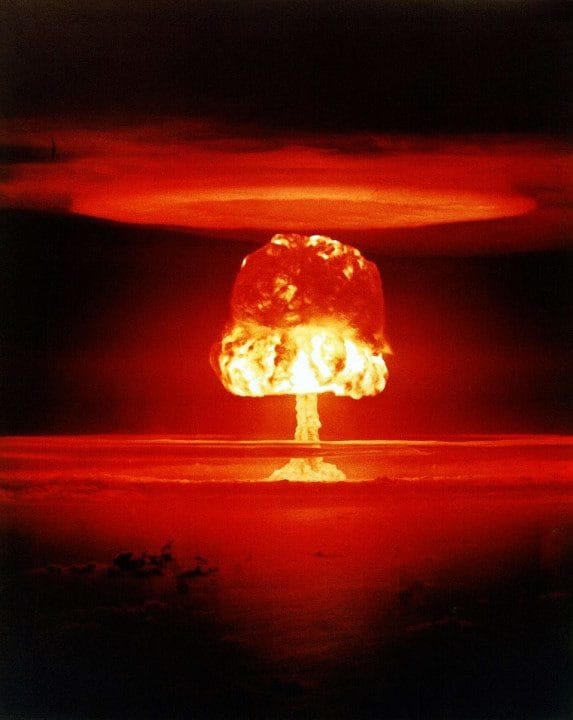

In Malmgren's story, Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay forcefully argues–in front of assembled top brass in a Pentagon war room–for a nuclear first-strike against targets in the Soviet Union, including Moscow--after which LeMay storms angrily from the room, having been defeated by Malmgren's rhetorical brilliance. In the eyes of some Malmgren admirers, the 27-year-old economist "saved the world" from nuclear destruction. It is quite a story.

Before we look more closely at the details of this Malmgren tale, it is necessary to spend some time reviewing the historical context. I am old enough to have lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis and to remember it. When I started this journalistic project, I thought that I already knew a fair amount about the episode. I found that much of what I thought I knew was wrong. Much of what Harald Malmgren thought he knew, when he made up his war room story many years after the actual crisis, was also wrong.

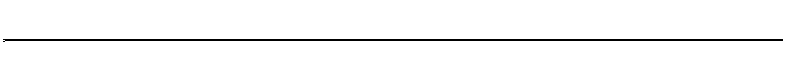

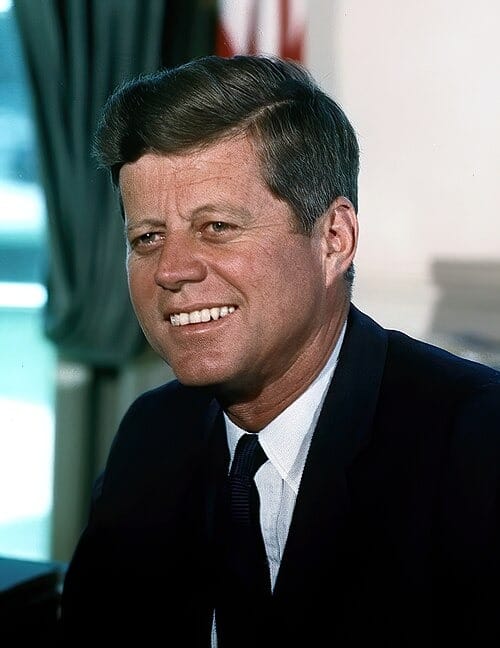

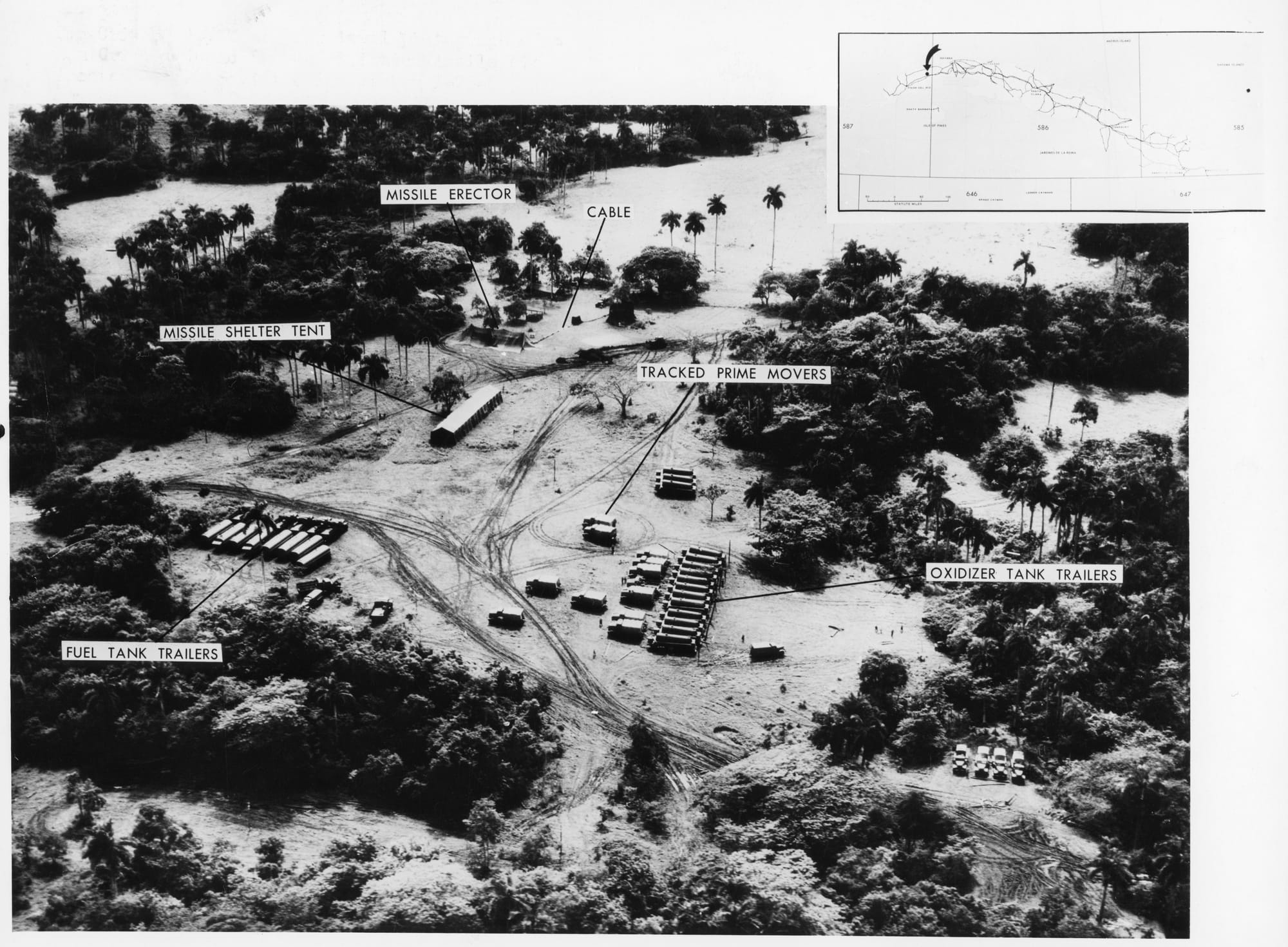

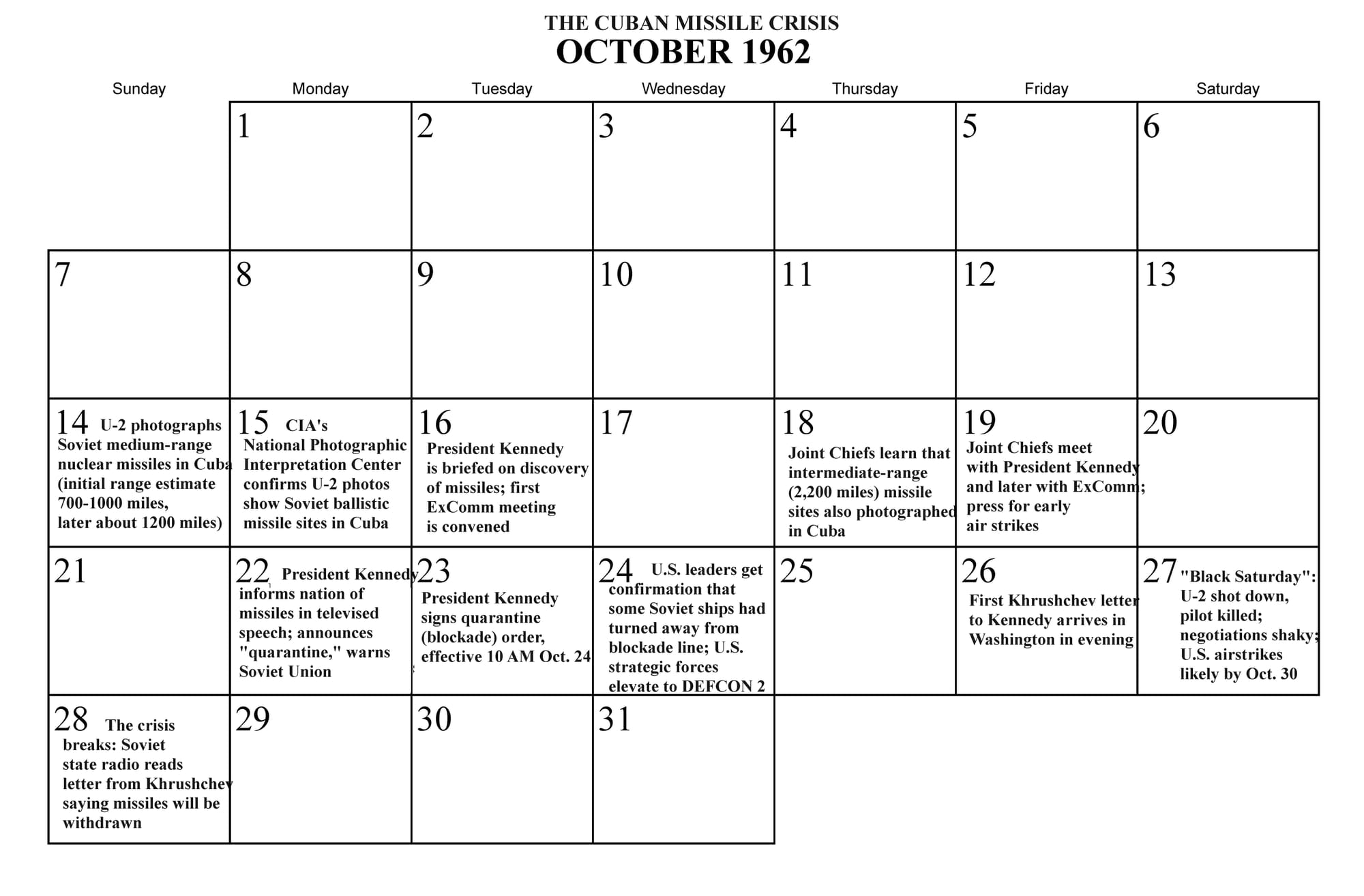

The Cuban Missile Crisis began to unfold on Sunday, October 14, 1962, when an American U-2 reconnaissance flight over Cuba revealed Soviet construction of bases for medium-range ballistic missiles. These were trailer-carried mobile missiles initially estimated to have a range of 700 to 1,000 miles, sufficient to reach Atlanta, Georgia (but soon reassessed to have a range of 1,200 to 1,300 miles, sufficient to reach Washington, D.C.).

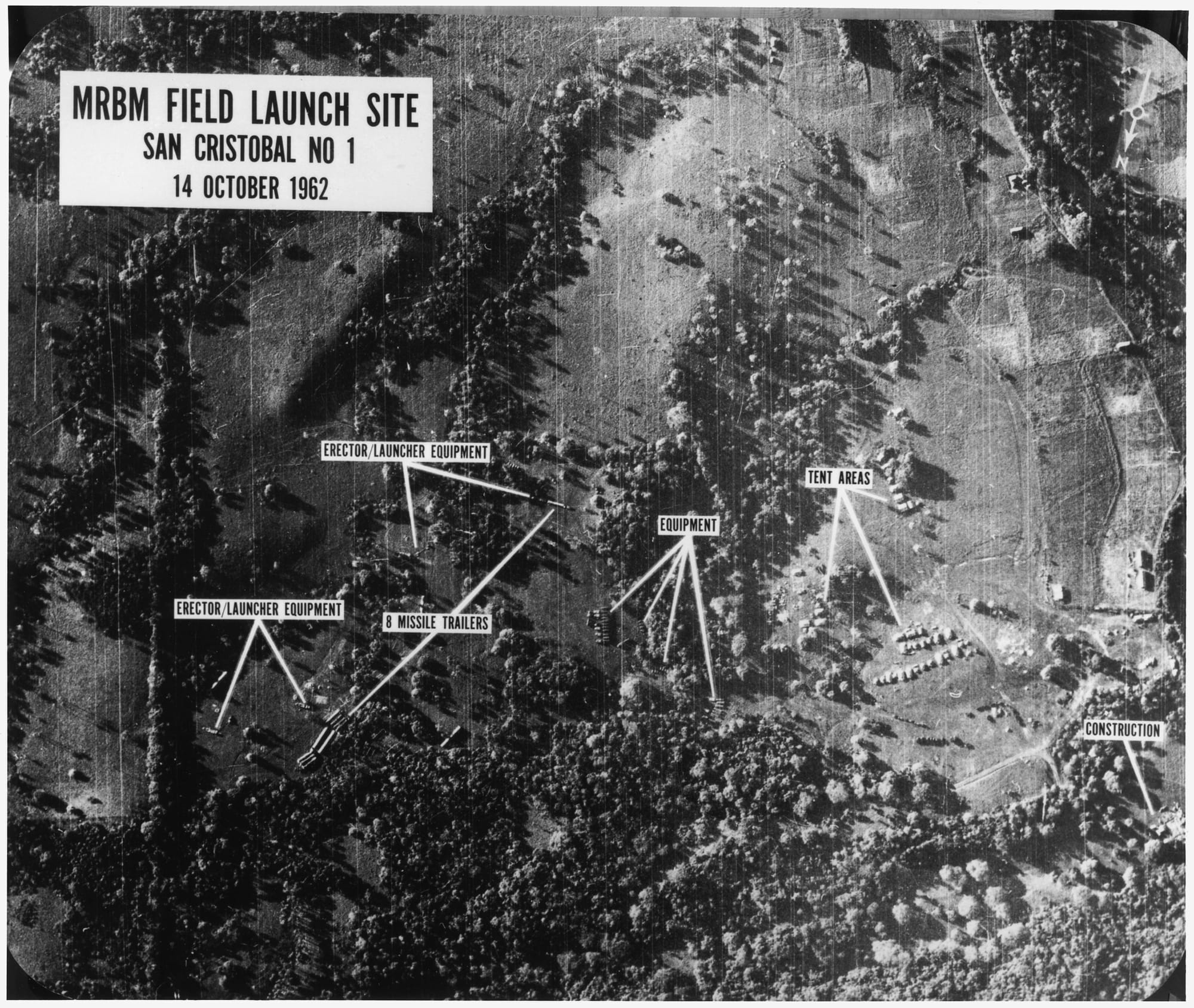

After intelligence analysts were certain of what they saw in the photos, President John F. Kennedy was informed of the discovery on the morning of October 16. He quickly convened a select group of senior advisors to deliberate regarding the U.S. response. This body came to be known as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm. The 14 "core" members (as formally designated by National Security Action Memo 196 on October 22) included Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, CIA Director John McCone, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Maxwell Taylor, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, and others. More than a dozen other men, such as Undersecretary of State George Ball and former ambassador to the Soviet Union Llewellyn Thompson, attended one or more meetings by invitation, often playing significant roles.

The 13 days from October 14 through October 28 are considered the core period of the Cuban Missile Crisis. There is probably no short period of 20th Century U.S. history that has been studied in such minute detail as that thirteen-day period. In 1988 McGeorge Bundy, President Kennedy's national security advisor, wrote, "Forests have been felled to print the reflections and conclusions of participants, observers, and scholars." (Danger and Survival, 1988, p. 391) But Bundy wrote that even before the greatest single trove of critical insider information had become public: actual audio recordings of most of the ExComm strategy sessions held throughout the crisis, and for weeks after the maximum peril had passed.

It was first revealed in 1973 that President Kennedy had maintained a secret taping system and had used it to record nearly all of the ExComm meetings, as well as an October 19 meeting he held with the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Of the ExComm participants, only the President–and probably his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy–knew of the existence of the recording system in 1962.

The recordings of the ExComm meetings were declassified and made available to researchers in stages, beginning in 1983. It appears that the last of the tapes from the critical thirteen-day crisis period were made public in 1997.

In addition to the many hours of ExComm recordings, many of the participants in high-level deliberations during the crisis later wrote books, participated in oral-history interviews, or otherwise related in detail their experiences during the crisis. Many sensitive documents have been declassified and thoroughly analyzed by scholars. Indeed, the entire huge body of material has been sifted through and debated by generations of scholars and journalists. We know a very great deal about who was saying what to whom among the nation's senior political and military leadership on every day of the crisis.

During the early days of the crisis, the ExComm weighed various diplomatic and military options. The military leadership and much of the ExComm membership were soon urging President Kennedy to authorize massive air strikes (non-nuclear!) on the missile sites and other military assets in Cuba, to be executed as early as October 23, likely followed by a U.S. invasion of the island. President Kennedy seriously considered air strikes and invasion from the start, but he also pursued multiple alternative paths–even after additional U-2 reconnaissance flights over Cuba ominously revealed that the Soviets were also rapidly constructing fixed sites for intermediate-range ballistic missiles with a range of up to 2,200 miles. These were missiles capable of carrying exceedingly destructive thermonuclear warheads to most of the continental United States.

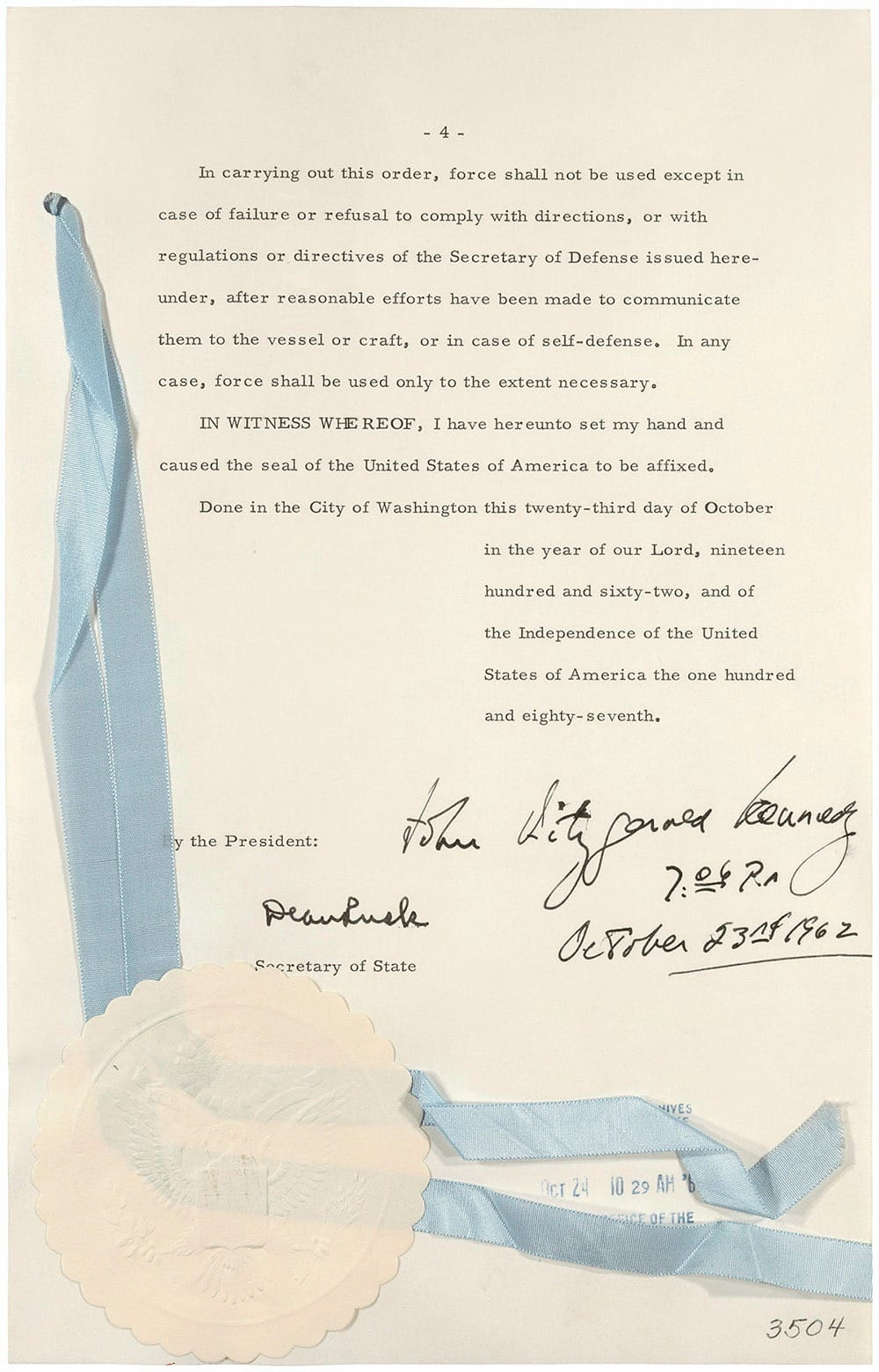

After nearly a week of the secret ExComm deliberations, on the evening of Monday, October 22, President Kennedy gave a televised address in which he announced the discovery of the missiles and his decision to impose a naval "quarantine" (blockade) to prevent further Soviet deliveries to Cuba.

In the speech, Kennedy said, "It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union." [italics added for emphasis] However – and this is very important in evaluating the claims made by Harald Malmgren a half-century later– I have found no historical record of anyone in the nation's political leadership or senior military leadership, at any point during the Cuban Missile Crisis, advocating or presenting as an option a nuclear first-strike on the Soviet Union, or even on Cuba.

The President's televised speech was followed by tense standoff between the two superpowers. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev denounced the quarantine as an act of aggression. Kennedy and Khrushchev began exchanging messages, but tensions continued to escalate. On October 24, the commander of the Strategic Air Command (SAC), General Thomas Power, raised the SAC alert level to DEFCON 2—one notch under the war level, and the highest level of readiness ever reached during the Cold War. Hundreds of thousands of troops, including airborne divisions, Marine units, and National Guard and Reserve units, were mobilized to prepare for an invasion of Cuba if the President gave the word. This mobilization was visible to the world.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff, as well as many of the President's civilian advisors on ExComm, pressed for the air strikes-then-invasion approach throughout the crisis. Kennedy realized that circumstances might eventually leave him with no politically feasible alternative to that course of action, but he was determined to exhaust all options to avoid armed conflict. Throughout the crisis, Kennedy remained acutely aware that U.S. attacks on the missile sites in Cuba would certainly kill many Soviet personnel (there were about 50,000 Russians in Cuba at the time), and would risk setting in motion a chain of escalation that could easily end in a full-blown nuclear exchange. Early on, Kennedy made it clear to his advisors that he would seek any feasible path to avoid such a spiral into a nuclear exchange, which he said would be "the final failure." [1] [2]

On the evening of Tuesday October 23, President Kennedy signed the formal order for a naval "quarantine" (blockade), to take effect at 10 AM the next day. At 7 AM on Wednesday October 24, U.S. leaders received word that several Soviet ships had already turned away to avoid the blockade line. Still, tensions continued to ratchet up each day that followed. By Friday, October 26, the situation had reached a critical juncture. Several Soviet missile sites in Cuba appeared nearly operational, and intelligence indicated continued construction and military activity. That morning, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a private letter offering to remove the missiles in return for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba. Though considered conciliatory, the offer soon was followed by a second, less conciliatory public message with inconsistent terms.

Saturday, October 27 is generally considered the most dangerous day of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and is sometimes referred to in the literature as "Black Saturday." That morning, a U-2 reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba by a Soviet surface-to-air missile, killing the pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. Although the missile was fired by decision of local commanders, many in ExComm and the Pentagon assumed the act had been authorized by Moscow, and viewed the shootdown as a deliberate escalation. Again, Kennedy was urged to proceed quickly with the airstrike-invasion option; the military mobilization preparatory to an invasion was in full motion. Compounding the tensions, another U-2 accidentally violated Soviet airspace over western Russia, prompting a futile chase by Soviet fighter jets. In the afternoon, U.S. warships had a tense confrontation with a Soviet submarine; unknown to the Americans, the submarine was armed with a nuclear torpedo. Also on this day, Cuban Premier Fidel Castro explicitly urged Khrushchev to order a general nuclear strike on the United States when the anticipated invasion of Cuba began.

Late on the Saturday October 27th, President Kennedy had his brother Bobby transmit a message to Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, proposing a two-stage deal: The Soviet Union would promptly withdraw its missiles from Cuba, in full public view. There also would be a strictly private understanding that months later the United States would quietly remove its Jupiter nuclear missiles from Turkey, but without ever acknowledging any connection between the two events.

Unbeknownst to Kennedy, Khrushchev had already decided to withdraw the missiles from Cuba, based merely on a U.S. no-invasion pledge, but Khrushchev was delighted to also receive the back-channel Jupiter missile concession. For his own domestic political reasons, Khrushchev later misrepresented the offer transmitted through Dobrynin as decisive. [3]

The acute crisis ended on the morning of Sunday, October 28, when a state announcer on a Soviet radio station read a letter from Khrushchev addressed to President Kennedy in which the Soviet premier said, "I appreciate your assurance that the United States will not invade Cuba. Hence we have ordered our officers to stop building bases, dismantle the equipment, and send it back home. This can be done under UN supervision." The world experienced profound relief as fears of imminent nuclear conflict receded.

Although negotiations continued for several weeks over some subsidiary issues, such as the presence of nuclear-capable bombers in Cuba and verification procedures, the Cuban Missile Crisis as such ended on Sunday, October 28.

HARALD MALMGREN'S STATUS AT THE TIME OF THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS: MALMGREN-WORLD VERSUS REAL WORLD

Above, I described the real-world stage on which Harald Malmgren, in his later years, wrote a script in which he placed himself in the midst of the top-level Pentagon action, and (as in most of Malmgren's tall tales) cast himself as a prime mover of events. The narrative has evolved over the years and has been recorded in varied forms, but for convenience here I will refer to the variants generically as "the war room story."

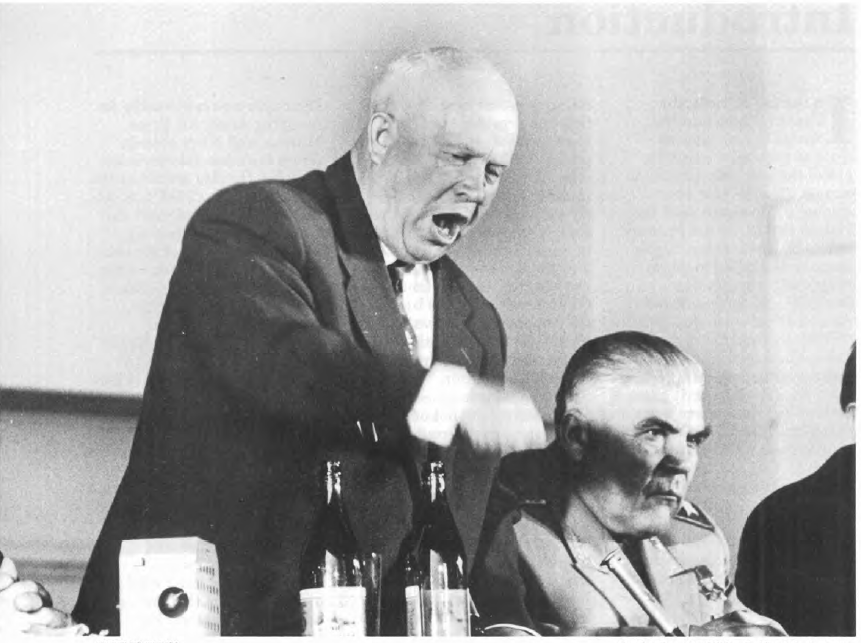

Malmgren (who died on February 13, 2025, at age 89) offered a bare-bones version of the story in a December 22, 2024 post on X (previously known as Twitter): "In the critical hours of Cuban missile crisis on final day just before Kruschev [sic] backed away, Curtis LeMay wanted authority to make 'surgical nuclear strikes on USSR to teach Soviets a lesson'. I persuaded rest of attendees to back off if Kruschev did. He angrily stormed out."

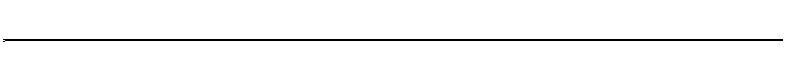

Those who have regarded Harald Malmgren as a credible narrator accepted the war room story at face value. Some have gone a big step further and lauded Malmgren as the savior of civilization, based on this specific story. For example, Harald's eldest daughter, Pippa Malmgren, wrote in a February 14, 2025 post on X: "At age 27, he successfully prevented General Curtis LeMay and the Joint Chiefs from dropping a nuclear weapon on the Soviet Union during The Cuban Missile Crisis, thus averting a nuclear catastrophe." Jesse Michels, who on April 22, 2025 posted a 3.8-hour YouTube video based on an extended interview with Harald Malmgren (viewed 670,000 times in the first month), dedicated that video to "Harald Bernard Malmgren: The Atomic Whiz Kid (Who Saved the World)."

To understand the Malmgren war room story, one must first be somewhat familiar with Harald Malmgren's alternative history of his life. That idiosyncratic narrative had some touchstones in Malmgren's real history, but branched off into numerous elaborate fictions. I compared Malmgren's real history with some of the fictional spin-offs in a long article titled "Harald Malmgren: Real-world history versus grandiose fiction," published on May 20, 2025. Here, I summarize only those elements necessary to analyze the war room story.

In both the real-world and fictional narratives, Malmgren came to Washington in mid-1962 and took employment as an economist at the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a nonprofit think tank funded by military contracts. But in the fictional history, Malmgren said that his IDA position was just a formality–asserting without evidence that his real role right from the start was as a personal right-hand man to the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara.

Malmgren's friend Robbin Laird published Malmgren's account in June, 2024, as follows:

In the summer of 1962 senior White House and Defense Department officials invited [Malmgren] to join the Administration of President John F. Kennedy. He moved to Washington, D.C., to join the Institute for Defense Analyses (advisors to the Office of the Secretary of Defense), serving as head of the Economics Group of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Weapons Systems Evaluation Group (WSEG), in the Pentagon, and as aide to Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, functioning as liaison to the White House National Security Council. He became known at that time as one of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara's "Whiz Kids."

Laird quoted Malmgren directly as follows:

I got a personal call from the White House by McGeorge Bundy (National Security Advisor to President Kennedy) to invite me to come to work for the Administration as part of McNamara's team. I was immediately excited to be asked to join JFK's team of young new faces to help craft the launch of a new government aimed at putting World War II behind us and crafting a new agenda for America's role in the world. In formal paperwork I was hired to work at the Institute for Defense Analyses, but that was a formality as my assignments were to do official tasks for the Joint Chiefs and the Secretary of Defense on a variety of defense issues.

In a 2018 presentation in Ireland, Malmgren described his purported 1962 role this way: "I was the go-between between McNamara and JFK and McGeorge Bundy, who was the NSC [National Security Council] director." In a January 2025 interview with Jesse Michels, Malmgren said, "I was appointed liaison between McNamara and McGeorge Bundy and JFK–I mean, pretty critical job."

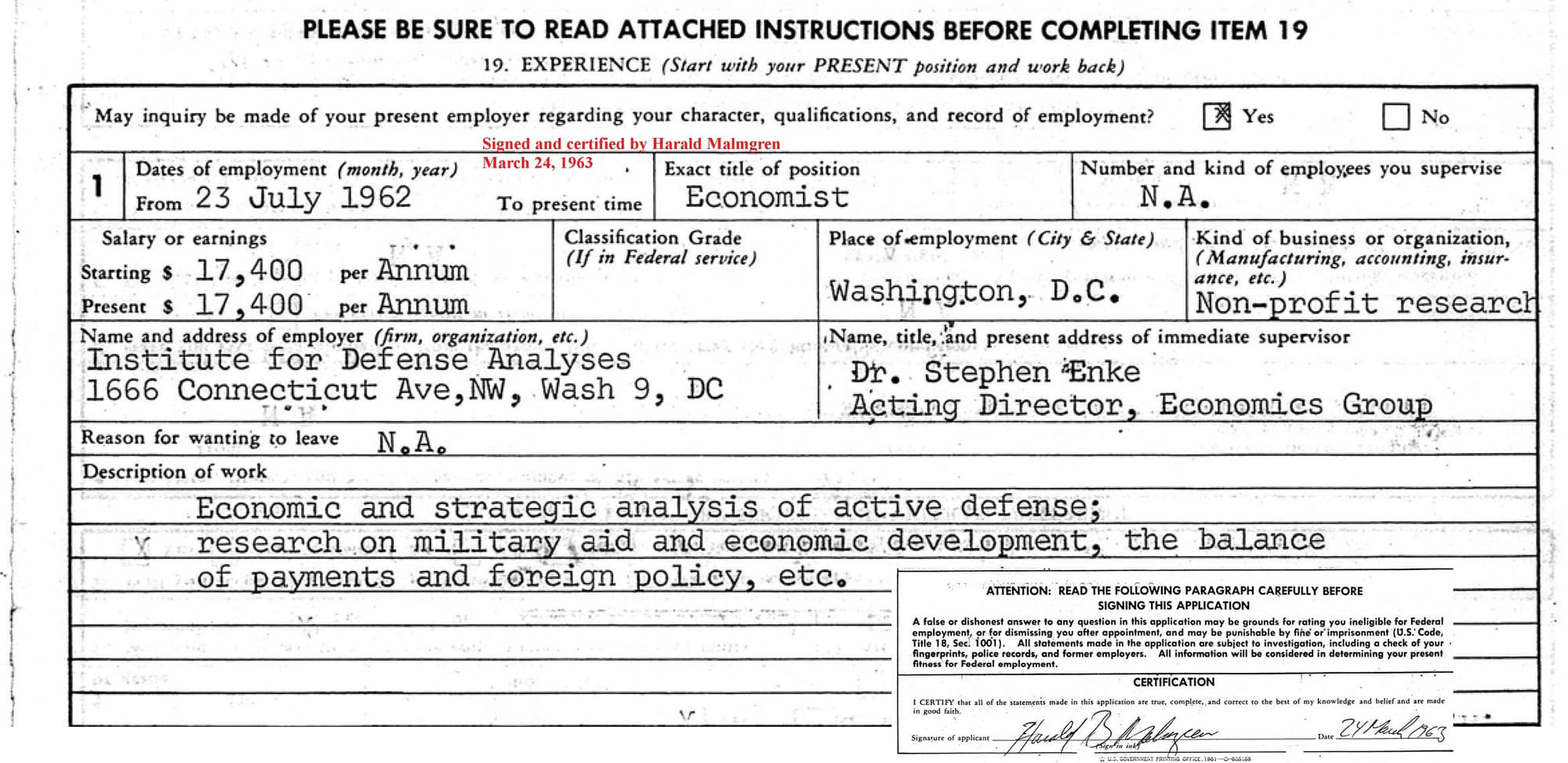

There is abundant documentation that beginning on July 23, 1962, Malmgren was a new-hire economist-researcher-analyst at the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), and that this organization employed him full-time for 27 months. In an application for federal employment that Malmgren signed and certified after eight months at IDA (March 24, 1963), he described his professional duties at IDA as follows: "Economic and strategic analysis of active defense; research on military aid and economic development, the balance of payments and foreign policy, etc."

This application and other documents embedded in my long article of May 20, 2025 demonstrate that Malmgren did not during the 1960s or 1970s even claim to have had any direct connection to Secretary McNamara, National Security Advisor Bundy, or President Kennedy himself.

(As I explained in that article, for the last month of the Kennedy presidency, Malmgren got a side gig as a part-time economist-consultant for the State Department, which later provided him with a very attenuated basis to claim to have been part of the Kennedy Administration–which of course is something very different from having been an "advisor to the president." Malmgren did not even mention this trifle in the employment history he submitted for use by the FBI for a 1971 security-clearance investigation. Malmgren did not become a full-time federal employee until October, 1964.)

On the March 1963 federal job application, Malmgren listed no supervisory responsibilities. However, on a second federal job application Malmgren signed on October 8, 1964--just two weeks before he left IDA for a full-time government job with the trade-representative office–Malmgren reported that he was "supervising work of some 20 economists and a dozen research assistants" as "head, Economics Group," indicating an intervening promotion (which suggests initiative and competence in his field).

However, even in October 1964, Malmgren remained pretty far down in the IDA hierarchy. In February 1964 IDA had a total staff of 524 persons, including 285 "professionals." In April 1964 IDA published a fancy, multi-colored 41-page report titled Activities of the Institute for Defense Analyses 1961-1964. The report contained many names of key IDA personnel, but Malmgren's name appeared nowhere. [4] This was not a very surprising omission in the real world, in which Malmgren was still just a 28-year-old economist-analyst heading a subdivision of the IDA's Economic and Political Studies Division (EPSD), which itself was one of six major IDA divisions. But Malmgren's absence from the report is surely inconsistent with his 2024-25 claims that by early 1963 he had been put in charge of developing a plan for defending the U.S.A. from Soviet ballistic missiles (not to mention being fresh off investigating a UFO knockdown-and-recovery on behalf of the President, National Security Council, and Secretary of Defense).

For the entire time that Malmgren was employed by IDA, the president of the organization was Richard Bissell, Jr., previously a deputy director of the CIA. Thus, throughout Malmgren's 27 months at the IDA, Bissell was the boss of Malmgren's immediate bosses. In his memoir Reflections of a Cold Warrior (Yale University Press, 1996), Bissell said that he–the IDA president--was completely out of the loop during the Cuban Missile Crisis. He wrote:

Although for years I had been intimately involved with matters relating to Cuba, I was unprepared for the disclosure that the Russians were initiating a capability to launch missiles from Cuba to the United States. On October 24, I wrote my son Winthrop at boarding school: "This has not touched IDA or me particularly because the kind of work we do is not related to immediate crises. Most of my friends in the government have been so busy that they have not even been free for lunch. All in all, I feel very much an outsider. (page 232)

So consider: Richard Bissell, the seasoned Cold War leader and IDA president– during the acute phase of the crisis, privately told his own son that he (Richard) was being kept "an outsider" as to what was going on. Bissell also told his son that the IDA as a whole had no involvement. And yet in the Malmgren story, at the critical hour, the 27-year-old IDA new-hire economist was a figure of authority in the war room, among members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. This does not compute.

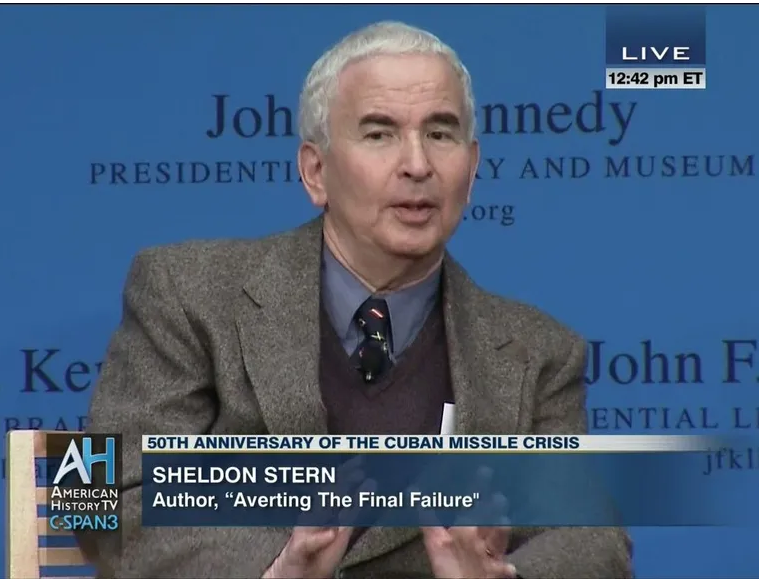

Sheldon Stern, Ph.D., former historian for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (from 1977-2000) and the author of three authoritative books on the Cuban Missile Crisis, told me:

In 1981, as the Historian for the J.F. Kennedy Presidential Library, I was assigned to listen to and evaluate the classified Cuban Missile Crisis tapes in preparation for their eventual release. I heard all fifty-nine days of CMC recordings, many other related tapes, and read hundreds of relevant documents. Harald Malmgren's name was never heard nor cited. Malmgren's claim to have been appointed as 'liaison between McNamara and McGeorge Bundy and JFK' is ludicrous. There is no such record at the JFK Library on tape or on paper. [email to author][5]

HARALD MALMGREN'S WAR ROOM STORY IN DETAIL

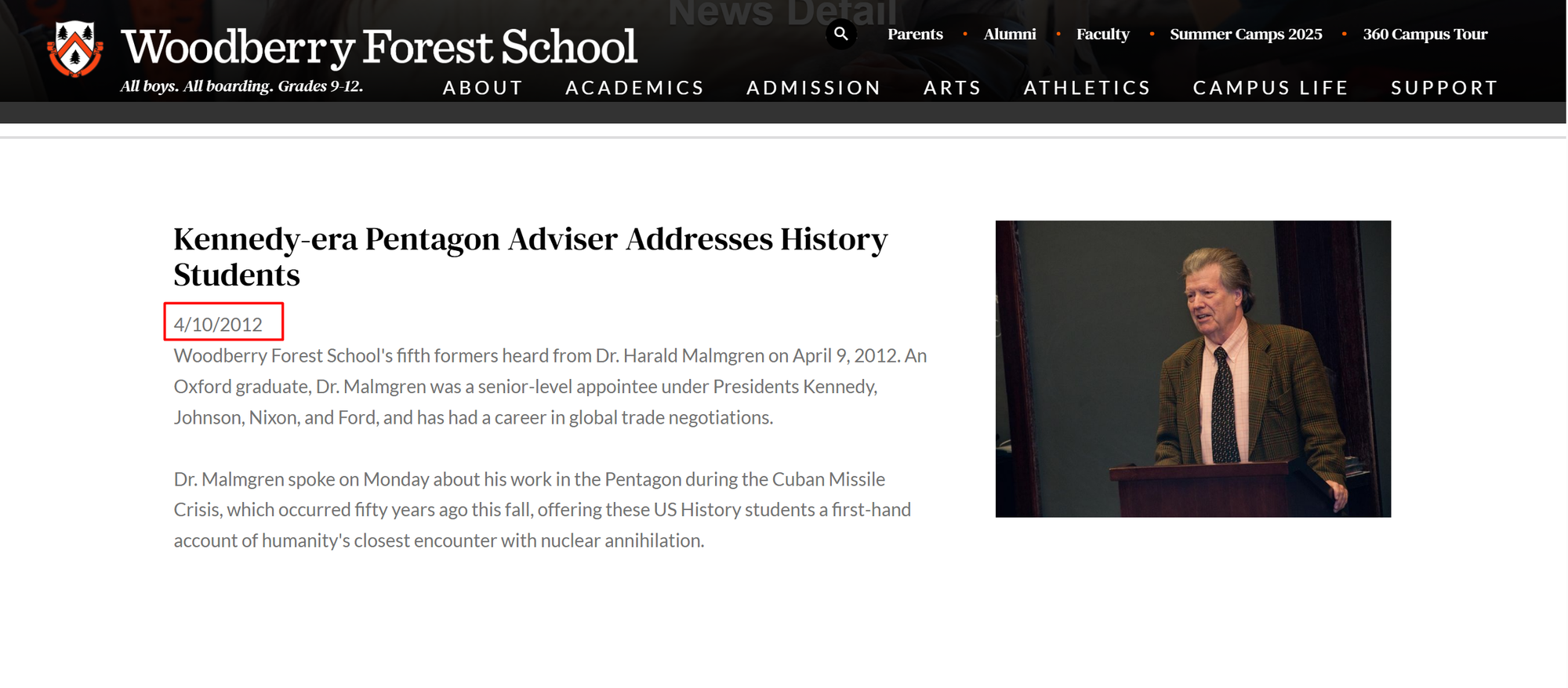

I do not know when Harald Malmgren first began portraying himself as a key actor in the Pentagon during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The first reference I found to Malmgren speaking publicly specifically about the Cuban Missile Crisis dates to 2012, in a brief notice about a presentation to a boarding school. Although I do not know what he said on that occasion, I note that the school's summary of the event contained the claim that Malmgren had been "a senior-level appointee under [President] Kennedy," which was false, and might have reflected information provided by Malmgren.

The earliest recorded version of the war room story that I found was told by Malmgren during the Kilkenomics festival in Kilkenny, Ireland, in November 2018. (This is an annual event that bills itself as "the world's first economics and comedy festival.") The festival organizers posted on YouTube an eight-minute segment showing Harald Malmgren on stage, telling a version of the war room story. The video is here. A verbatim transcript is embedded below.

Here is a key part of the 2018 exchange between Malmgren and Kilkenomics organizer David Williams:

Harald Malmgren: I was the go-between between McNamara and JFK and McGeorge Bundy, who was the NSC director. And it was a time when Jack Kennedy brought to Washington a lot of young, fresh minds, most of them economists. I was in that crowd. And our job wasn't to tell people with experience what to do, but ask a lot of questions, get people to think outside the box. And I was there conveying questions like, okay, if we go, what do we hit? I mean, if we hit Moscow and it only goes on a few hours and we want to stop, who do we talk to?

David McWilliams: At the end?

Harald Malmgren: At the end, yeah. And a bunch of generals, including the Strategic Air Command chief over in the Pentagon [identified later by Malmgren as General Curtis LeMay, although he was actually USAF Chief of Staff at the time, above the SAC commander] said, “Well, of course we have to go and not worry about that. We've got to kill those guys in Moscow. They created all this trouble.” And I said, but yeah, but are we ready to go over there and govern Russia? And everybody said, no, no, we're not planning on that. I said, well then if you want to stop, who do you talk to? Why don't we just agree that hitting Moscow is the last thing we want to do? And then one of the generals said, “That's the best damn question that anybody's ever raised.” He said, “And let's leak that to the Russians. And so they won't hit Washington either, and we're all safe.” [general laughter]

In a January 2025 long interview with Jesse Michels, Malmgren told a much longer and more detailed version of the war room story, most of which is found between minutes 36 and 53 of the video. A verbatim transcript of that entire segment is embedded below, along with short video excerpts extracted under Fair Use doctrine.

Harald Malmgren describing his claimed 1962 face-off with General Curtis LeMay to Jesse Michels, January 2025. Fair Use under 17 U.S. Code § 107 for noncommercial purposes of investigative journalism, scientific research and debate, education, commentary, and criticism.

Here are some of the key passages from Malmgren's 2025 narrative:

Harald Malmgren: I was appointed liaison between McNamara and McGeorge Bundy and JFK– I mean, pretty critical job...Sunday, the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolds. And I get a call, “Bob wants you to work directly with a smaller group in the War Room.” I said, “What's the War Room?” “It's where the generals meet and decide, go/no go. Because they have the weapons, the White House doesn't have them.

Jesse Michels: So this is Bob McNamara, and he wants you to meet...

Harald Malmgren: He wanted me to be there in that room as his guy. They would know I'm his guy. And I said, yeah, they're not going to be eager to hear from this young squirt. He said, “Don't tell them what you think should happen. Ask them a lot of questions. Your job is to slow them down, reduce the heat in the room. Get everybody more calm. If you just keep asking questions and make them think, you'd be surprised how far that goes. And it buys us time and takes the pressure off from them.” Because there are some people in that group (I didn't realize it was Curtis LeMay they were worried about) who wants to go ahead and punish Russia for even trying.

Further on:

Anyway, I didn't know what I was up against, or it might have scared me, but it didn't. So I said, well, all the rest of us, let's contemplate the options. We slowly talked. And then it turned out that we got word the Russians stopped the boats at the point of quarantine. And I said, “Can we agree that we should back off? Khrushchev has just backed off.”

And Curtis LeMay said, “No way. We've got to teach them a lesson, messing with us, they have to have something to remember. We need some surgical strikes on Russia. It doesn't have to be population-oriented, but we need to make it painful.”

And I said, “But that leads us back into will they think that this is just the beginning of Armageddon–again, we simply haven't had a discussion. We have no communication channel to deal with that. It doesn't make sense. It seems to me backing off for now and letting the discussions continue, how do we avoid this being the preference?" All the generals agreed. And the one that had called his wife pushed the button, his aide came in, and he said, “Call Mary back. Tell her, unload the car.”

Pippa Malmgren: But you also made a suggestion that if you hit Moscow, there wouldn't be anybody to negotiate with. And further, if you let it leak to the Russians that you wouldn't hit Moscow, maybe they wouldn't hit Washington. And everybody in the room just loved that.

Jesse Michels: And if I remember correctly, you kind of rhetorically backed them into a corner where you say, “What would be your prime target first?” And then they say, “Moscow.” And then you say, “Oh, if it's Moscow, then you can't talk to anybody at Moscow. There's nobody to negotiate with.”

Harald Malmgren: Yes, we went through that. Because I said, it's madness. If you're going to start something and you need to stop in that system, there's only one point of decision. If you hit Moscow, there's no one to talk to.

Jesse Michels: And then that's at that point, right, LeMay storms out and gets all angry? Is that right?

Harald Malmgren: Yeah, no, he literally got up, slammed his papers down, said, “I refuse to go on with this.”

[Short segment of Harald Malmgren further elaborating over phone with Michels]:“That man was a [inaudible word] maniac. But I have to tell you, I did not buckle.”

Michels: “No, I know you didn't.” [6]

EXAMINATION OF KEY ELEMENTS OF MALMGREN'S WAR ROOM STORY

Setting aside the demonstrably fictional character of Malmgren's underlying claims about the positions and powers he held in 1962, which I have already discussed, I turn now to some of the things that are wrong specifically with Malmgren's war room story.

Malmgren badly garbled the well-established basic chronology of the Cuban Missile Crisis

One difficulty in unwrapping Malmgren's story is that he never gave a calendar date for the purported war room meeting. This is perhaps understandable, because no real-world date corresponds even approximately to the situation that Malmgren described in any version of his story. In Malmgren's narrative, three major developments occur over a period of hours–developments that, in a distorted fashion, reflect events that in the real world happened over a period of four days.

In Malmgren's story, the fateful meeting occurs at "the end" of the Cuban Missile Crisis, "in those final hours [when the] agitation level was high." In his December 22, 2024 tweet, reproduced above, Malmgren said specifically that the gathering occurred "in the critical hours of Cuban missile crisis on final day just before Kruschev [sic] backed away..." [boldface added for emphasis]

In the story, the Joint Chiefs of Staff are meeting to decide on military action, which may be only hours away. The 27-year-old economist is an active participant in a debate with the Joint Chiefs because he is identified as Secretary McNamara's "guy."

In Malmgren's telling, the tension is high because Soviet ships were approaching a blockade line around Cuba. In front of everybody, a "senior general" sends his wife a message to drive to Maine "as fast as you can." Suddenly word arrives that the Soviet ships have stopped–Khrushchev has, in Malmgren's words, "backed off." Yet General Curtis LeMay pushes for nuclear strikes "to teach them a lesson"–nuclear strikes on Moscow, or if not Moscow, then at least on other strategic sites within the Soviet Union. After Malmgren's remarks deflate the general's evil scheme, LeMay leaves in a fury. At that point, both the LeMay crisis and the Cuban Missile Crisis have ended. The unnamed "senior general" sends a second message to his wife, informing her that it is no longer necessary to leave Washington.

So goes the story.

In reality, the Kennedy-ordered blockade took effect not in "the last hours" of the Cuban Missile Crisis, but on Wednesday, October 24, at 10 AM. Top U.S. leaders received word early that day (October 24) that a number of Soviet ships already had changed course to avoid approaching the blockade line. That development, while welcome, certainly did not resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis–far from it. Indeed, tensions continued to increase progressively over the four full days that followed (Wednesday through Saturday, October 24 through 27).

The situation appeared most dire on Saturday, October 27, "Black Saturday." Surveillance photography showed that Russian troops in Cuba had brought some of the ballistic missiles to the point of being operational, or nearly so. A U-2 was shot down over Cuba by a Soviet missile and the pilot killed, perceived by American leaders as a deliberate act of escalation by the Soviets. Negotiations were confused and had led to no resolution. Secretary McNamara said he felt that an invasion was "almost inevitable," and the Joint Chiefs were strongly urging that airstrikes commence no later than Tuesday, October 30. President Kennedy apparently felt that by October 30 he would have no other viable option.

This peak tension did not break on "Black Saturday," October 27–the President and other American leaders went to bed that night greatly fearing what was to come. But the next morning, Sunday, October 28, a Soviet state radio announcer read a letter from Khrushchev to Kennedy, in which the Soviet leader said he would withdraw the missiles from Cuba. President Kennedy told his personal assistant, David Powers, "I feel like a new man now. Do you realize that we had an air strike all arranged for Tuesday? Thank God it's all over." [7]

Like a Hollywood script writer who freely takes gross liberties with historical facts for cinematic narrative purposes, Malmgren simply ignored all of that real history. In his story, the ships are approaching the blockade line on the very eve of U.S. military action, and their retreat is the act that resolves the crisis–all completely ahistorical. Malmgren mushed together into one meeting highly distorted versions of events that actually happened on October 24, October 27, and October 28. [8]

Cuban Missile Crisis historian Sheldon Stern noted several of the glaring departures from the historical record:

Malmgren wrote that they were in “the final hours waiting to see if the ships are going to stop or not.” That very well-documented event happened on October 24–three days before the final peak day of the crisis on Saturday October 27....Harald Malmgren also made the ludicrous claim that “the history books have omitted” the critical role of Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. In fact, Dobrynin's secret negotiations with RFK were invaluable and covered in detail in all the key sources; Dobrynin also wrote his own fascinating and candid memoir. (emails to author)

Appendix A reproduces authentic summary notes of the meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that occurred on "Black Saturday," October 27. Unsurprisingly, the real-world record of the Joint Chiefs' deliberations has virtually no resemblance to the Harald Malmgren story.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, nobody really proposed first-use of nukes by the United States

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Joint Chiefs of Staff consistently argued for conventional kinetic (not nuclear) air strikes on the Soviet ballistic missile sites and other military sites, in Cuba. But I found no reference to any authentic historical record indicating that General LeMay or any other military authority advocated the first-use of nuclear weapons against sites in either the Soviet Union or in Cuba, at any point during the Cuban Missile Crisis. [9]

It is noteworthy that during the period of approximately 1949-1955, there is credible evidence that LeMay, internally within the military, argued for a policy of a "preventive" nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union. His reported rationale was that the U.S. then still held overwhelming nuclear superiority with advanced bombers, but if the Soviet Union developed its nuclear capacity unimpeded it would eventually be capable of launching a devastating attack on the United States. These views did not gain broad military support and were never formally proposed to civilian authorities, although Presidents Truman and Eisenhower proactively rejected the concept of preventive war (in 1950 and 1953, respectively). This historical backdrop provides no support at all for the fictional 1962 position imputed to LeMay by Malmgren. By 1962, strategists agreed a full nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union could kill on the order of 75 million Americans. If a nuclear exchange had occurred in 1962, “You’re talking about the destruction of a country," President Kennedy observed when he met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff on October 19, 1962.

Journalist Warren Kozak, author of LeMay: The Life and Wars of General Curtis LeMay (Regnery, 2009), told me, "I know LeMay wanted a confrontation with Cuba, along with all the members of Joint Chiefs, but once Kennedy decided to pacify the situation, LeMay, in my judgement, would have followed the orders of his commander-in-chief, as he always had. He may have griped about it, but he definitely would have followed orders." (email to author, June 10, 2025, italics added for emphasis)

Philip D. Zelikow, J.D., Ph.D., is Botha-Chan Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and co-author (with Ernest R. May) of The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis (1997; rev. 2001). After reviewing Malmgren's war room story, he told me:

Malmgren is a fantasist. I too have listened to the JFK missile crisis tapes in their full, classified form–and I’ve also examined the classified Department of Defense records on the crisis. And of course Ernest May and I were personally acquainted with a number of the relevant participants in the crisis, including both Robert McNamara and McGeorge Bundy. There are particular problems with Malmgren’s fanciful LeMay story if one knows more about the actual operational plans of the U.S. Air Force and the Strategic Air Command during this period. In the plans in place in 1962, there were certain situations, if a strike on the U.S. seemed imminent, in which the Strategic Air Command would very much have wished to conduct a massive preemptive attack on Soviet nuclear forces. But that has little to do with Malmgren’s colorful invention. (email to author, June 7, 2025)

Sir Lawrence Freedman is a very eminent military and strategic historian– Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King’s College London, and co-author of The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy (1981; 3rd edition 2019). He told me:

As you surmise his [Malmgren's Cuban Missile Crisis] claim is nonsense....There was a famous incident towards the end of the crisis when LeMay did argue for launching an air strike against Cuba anyway (but of course not a nuclear first strike) but this was dismissed by Kennedy. (email to author, June 6, 2025)

If U.S. first-use of nuclear weapons during the Cuban Missile Crisis had been urged by LeMay, or by anybody important, we would have heard about it many years ago.

If General LeMay had pushed the Joint Chiefs to recommend punishing the Soviet Union with a nuclear first-strike in October 1962, we would not be hearing about the encounter for the first time a half-century later, in interviews and tweets by the self-styled hero of the tale.

If the USAF Chief of Staff, or the commander of the Strategic Air Command (Gen. Thomas Power), or any other military leader at any point during the Cuban Missile Crisis had urged a nuclear first-strike on the Soviet Union–or even proposed such an action as a viable option–it would have become known immediately to the President and other top civilian leaders, and they would have talked about it among themselves. It also would have become common knowledge and very widely discussed during the ensuing decades.

In his televised speech on October 22, 1962, President Kennedy himself made it clear that the launch of any of the Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba would result in a full retaliatory nuclear attack directly upon the Soviet Union. Obviously, this is something entirely different from the proposal that Malmgren attributed to General LeMay, who supposedly wanted to "make surgical nuclear strikes on USSR to teach Soviets a lesson" even after Khrushchev had "backed off."

If LeMay really had argued with a McNamara aide about such a nuke-first proposal, in front of assembled top brass, that astonishing proposal and its reception would have come to light in the innumerable memoirs and oral histories that became available in ensuing decades. There also would have been references to it in contemporary sources, both official government documents (likely initially classified, but later declassified) and informal documents such as diaries, private correspondence to family members, and the like. [10]

Moreover, keep in mind that Malmgren claimed he was present at the war room meeting as the personal agent of Secretary McNamara ("They would know I'm his [McNamara's] guy."). Presumably the first thing Malmgren would have done after the remarkable clash with LeMay would have been to report back to McNamara about the encounter–after all, in the tale, McNamara had specifically warned Malmgren that some officers might want to "punish Russia for even trying." After Malmgren reported back to McNamara, the Secretary surely would have shared the report at the very next ExComm session. McNamara would have been negligent indeed if he had not informed the President and the rest of the ExComm that the hard-charging Air Force Chief of Staff was pushing for nuking Soviet sites, maybe even Moscow, and this even after Khrushchev had "just backed off."

Certainly there would have been nothing to inhibit McNamara from sharing that shocking information with the President or the ExComm; there is abundant historical evidence that there was no love lost between McNamara and LeMay. [11] [12]

But of course, neither the records of ExComm sessions nor any other credible historical source contains any discussion of any proposal by LeMay to launch a punitive nuclear first-strike on the Soviet Union during the Cuban Missile Crisis. That wild tale has a single source: Harald Malmgren, now well documented to have been a prolific confabulator of self-glorifying ahistorical tales.

The war room story displays Malmgren's characteristic narcissistic grandiosity, and contains multiple obviously implausible elements

Even if one knew nothing about Harald Malmgren's actual job history, and no details regarding the chronology of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Malmgren war room story incorporates multiple elements that, on first glance, are plainly implausible--in some respects, laughably so.

In the 2025 version, Malmgren sagely observed, "If you hit Moscow, there's no one to talk to." Golly, that boy had a mind like a steel trap. It is puzzling that some commentators seem to have no difficulty with the notion that until Malmgren pointed it out, it apparently had not occurred to the assembled generals and admirals that nuking Moscow might create difficulties in subsequently communicating with someone in Russia holding authority to end the conflict.

(Even more laughable in the 2018 Kilkenomics festival version, in which the generals are impressed by Malmgren's observation that if they hit Moscow, then they had better be prepared to take over governance of Russia.)

In Malmgren's 2018 version, after he points out the obvious, a top general remarks, "That's the best damn question that anybody's ever raised." This is inane. It is truly cringeworthy. But, it is also very on-brand for the Harald Malmgren we see in many interviews and tweets. A major theme of Malmgren's stories is that Harald is a Very Special Person. In the stories, Harald is not only the smartest person in the room–he may be the smartest person on the planet. Not that he characterizes himself that way, mind you, but all sorts of high-caliber people have verbally taken note of his extraordinary attributes, and Harald casually shares their judgments with us.

Malmgren's stories are replete with high-level people– such as MIT Corporation President Karl Compton, famed economist John Hicks, Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, storied CIA/IDA leader Richard Bissell, trade representative Christian Herter, and many others--expressing their amazement at Harald's singular abilities.

In these flights of imagination, Compton is astonished at Malmgren's command of esoteric concepts of physics at age 13 ("you see beyond the biggest minds") and tries to persuade him to immediately accept a free ride all the way through graduate school at MIT (Malmgren said he declined). Hicks decides Malmgren is an original thinker of the caliber that "only comes along every 30 or 40 years." Cornell University wins a bidding war among major universities by making Malmgren a full professor instantly after receiving his doctorate. [This is a proven fiction.] He was recruited for the Kennedy Administration because "I was like being somebody who was the number one draft for the NFA [sic]. [13] Of course, I did not think of myself that way but they decided they needed me.” [He actually did not get a full-time federal job until 1964.] Dobrynin arranges to sit next to Malmgren at a 1963 banquet because "he [Dobrynin] was interested in what was my way of thinking during this crisis," referring to the Cuban Missile Crisis. [Highly implausible.] Bissell tells Malmgren "you were the star" of the McNamara "whiz kids." [No evidence has surfaced that Malmgren had any direct connection with McNamara; he was not among the historically recorded McNamara "whiz kids."] The all-knowing supra-governmental MJ-12 had watched over Malmgren from the start. "They tracked him from a young age, he [Malmgren] says," according to Jesse Michels. "You were chosen," Christian Herter assures Malmgren. Many more such examples could be cited.

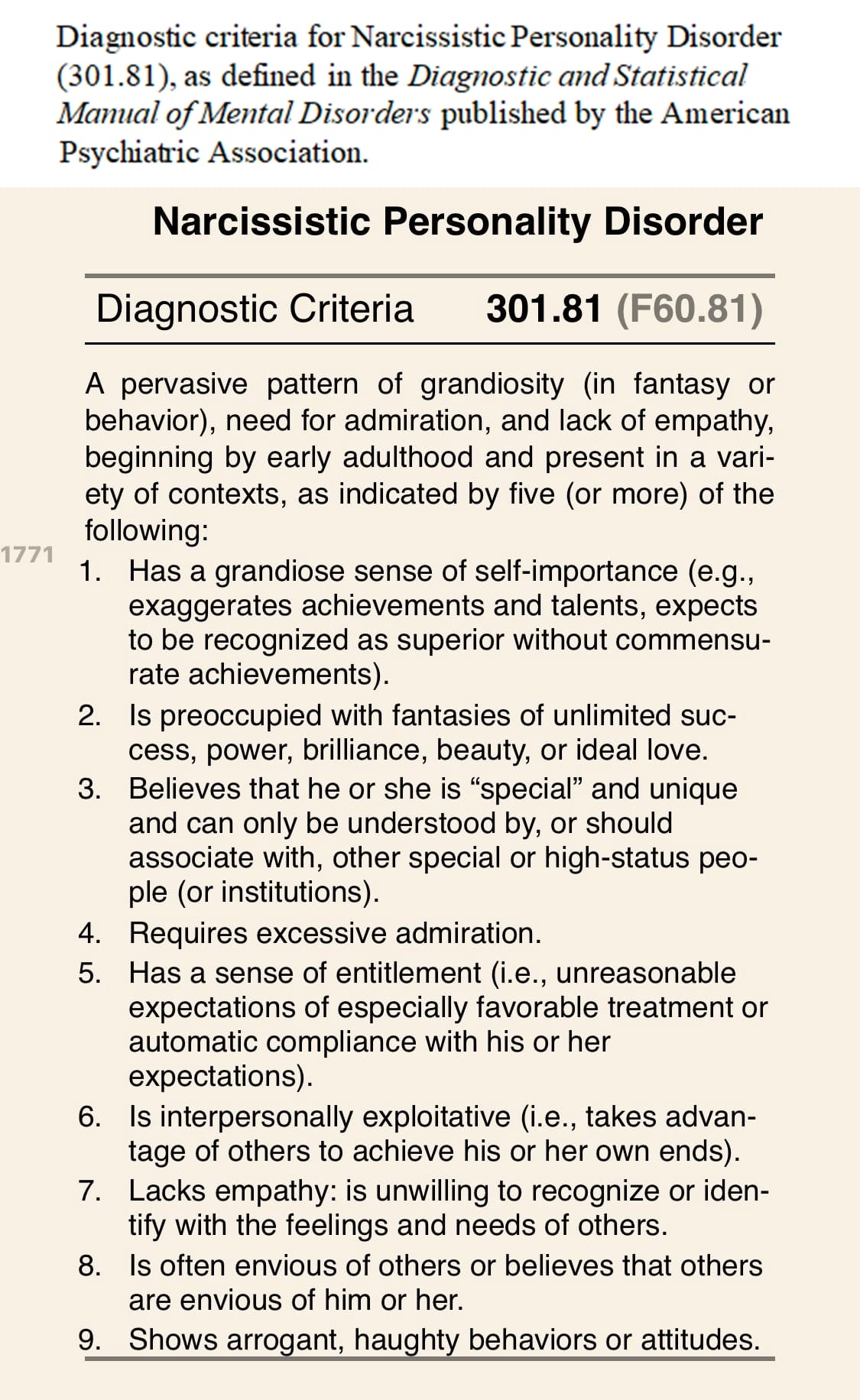

I remain baffled at why even some often-serious-minded people have failed to consider the infantile, and in my opinion pathological, content of many of Malmgren's narratives. Reviewing the criteria for "Narcissistic Personality Disorder" in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, based on the explicit content and presentation of numerous public utterances by Malmgren, it is my personal layman's opinion that he met the diagnostic threshold of "five (or more)" of the listed criteria, although not all nine.

The premise of the claim that Harald Malmgren "saved the world" is nonsensical, since General LeMay had no authority to launch a nuclear strike (even if the Joint Chiefs had agreed), and obviously President Kennedy would not have agreed to any such recommendation

Even without prior knowledge of the details of the Cuban Missile Crisis or of Harald Malmgren's personal history, it is a preposterous premise that whether a first-strike nuclear attack on the Soviet Union occurred was determined by the outcome of an argument between a service chief and a 27-year-old economist. The basic stage-setting for Harald Malmgren's tale (2018: "we have four hours to decide everything, and otherwise everything goes off") is implausible on its face.

Yet Harald Malmgren's promoters have proclaimed that when he verbally bested General LeMay (in his story), Malmgren "saved the world." For example, Harald's daughter Pippa posted on X on February 14, 2025, "At age 27, he [Harald] successfully prevented General Curtis LeMay and the Joint Chiefs from dropping a nuclear weapon on the Soviet Union during The Cuban Missile Crisis, thus averting a nuclear catastrophe."

Some other examples of such tributes will be found near the end of this article.

Yet even if General LeMay had actually made such a nuclear first-strike proposal (which he did not), and even if the Joint Chiefs of Staff had concurred (a bonkers premise), they had no authority "to [drop] a nuclear weapon on the Soviet Union." The most they could have done was recommend that course of action to President Kennedy.

Would Kennedy–who had for about ten days had resisted increasing pressure from both the Joint Chiefs and many of his civilian advisors to quickly launch non-nuclear airstrikes even on Soviet nuclear missile sites in Cuba–now have accepted LeMay-Joint Chiefs advice to launch a punitive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union? The question answers itself.

ARE THERE STORIES THAT SOME PEOPLE THINK ARE TOO GOOD TO CHECK OUT?

On the date of publication of this article (June 9, 2025), Jesse Michel's Malmgren video ("I touched a UFO!) has garnered 729,000 views in seven weeks. Considerably fewer people are going to read this article. Young Harald going toe-to-toe with "Bombs Away" LeMay and thereby saving the world is a cool story (as long as you don't analyze it too much, or at all). For many, reading or hearing about why it could not have happened and did not happen is just a buzzkill, and probably a manifestation of some vast conspiracy to bury heroic Harald's revelations.

“Falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it,” Jonathan Swift wrote in 1710. Truer words were never spoken. [14]

It seems that neither the ascertainable falsity of Malmgren's claims regarding his 1962 status, nor the glaring implausibilities in the war room story itself, gave the slightest pause to some people who decided to cast the one-time trade negotiator not as merely a "whistleblower," but as a veritable avatar and world-saver. Keep their unconstrained subjectivity and lack of critical discernment in mind the next time they tell you that something is so: They might just be feeding you another cool story that they thought was too good to check out.

(If any of the individuals quoted below have changed their opinion since the public statements that I quote, I would be happy to receive updated information; any communications that I receive containing such updated information on this subject I will regard as "on the record.")

Let's take a look at some examples:

"Harald Malmgren literally saved the world from nuclear devastation. Not an exaggeration," proclaimed Jesse Michels in a February 14, 2025 post on X. By April 22, Michels was hyping Harald's mythical achievement even further: "Harald is a hero who saved the world (and more than once)," he asserted on X. At least he left off the "not an exaggeration" disclaimer on the latter tribute.

Christopher Sharp, owner of the UFO-oriented Liberation Times blog, was equally effusive in a post on X on February 14, 2025, stating, "I think we can thank Harald Malmgren for our very existence in this world."

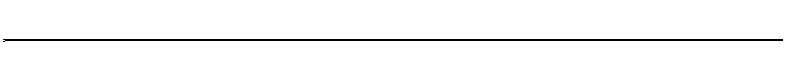

Ross Coulthart, correspondent for the NewsNation network and co-host of the Need to Know podcast, was only a shade more cautious in a post on X the same day, telling his viewers that Malmgren had been a "key junior staffer" to President Kennedy and "a great American, an unacknowledged hero who very likely played a major role in averting nuclear Armageddon." [15]

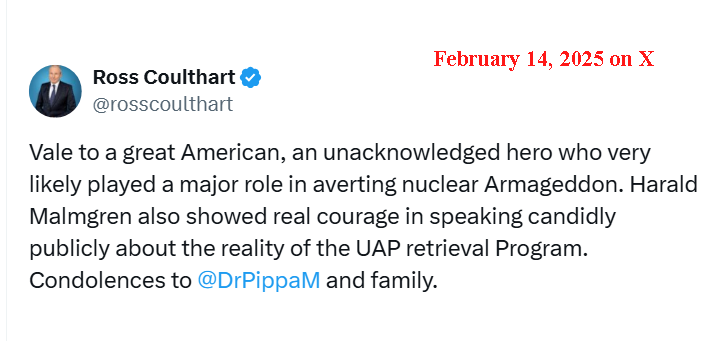

Matthew Pines is a strategic advisor to Skywatcher, an organization that bills itself as pursuing "a disciplined, data-driven approach...to separate fact from fiction" regarding "aerial activity." On April 22, 2025, Pines commented that Malmgren "saved human civilization" and also had shared "his first-hand knowledge regarding non-human intelligence and related technologies."

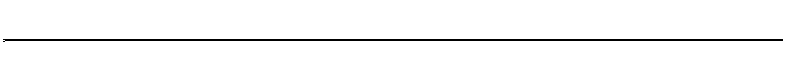

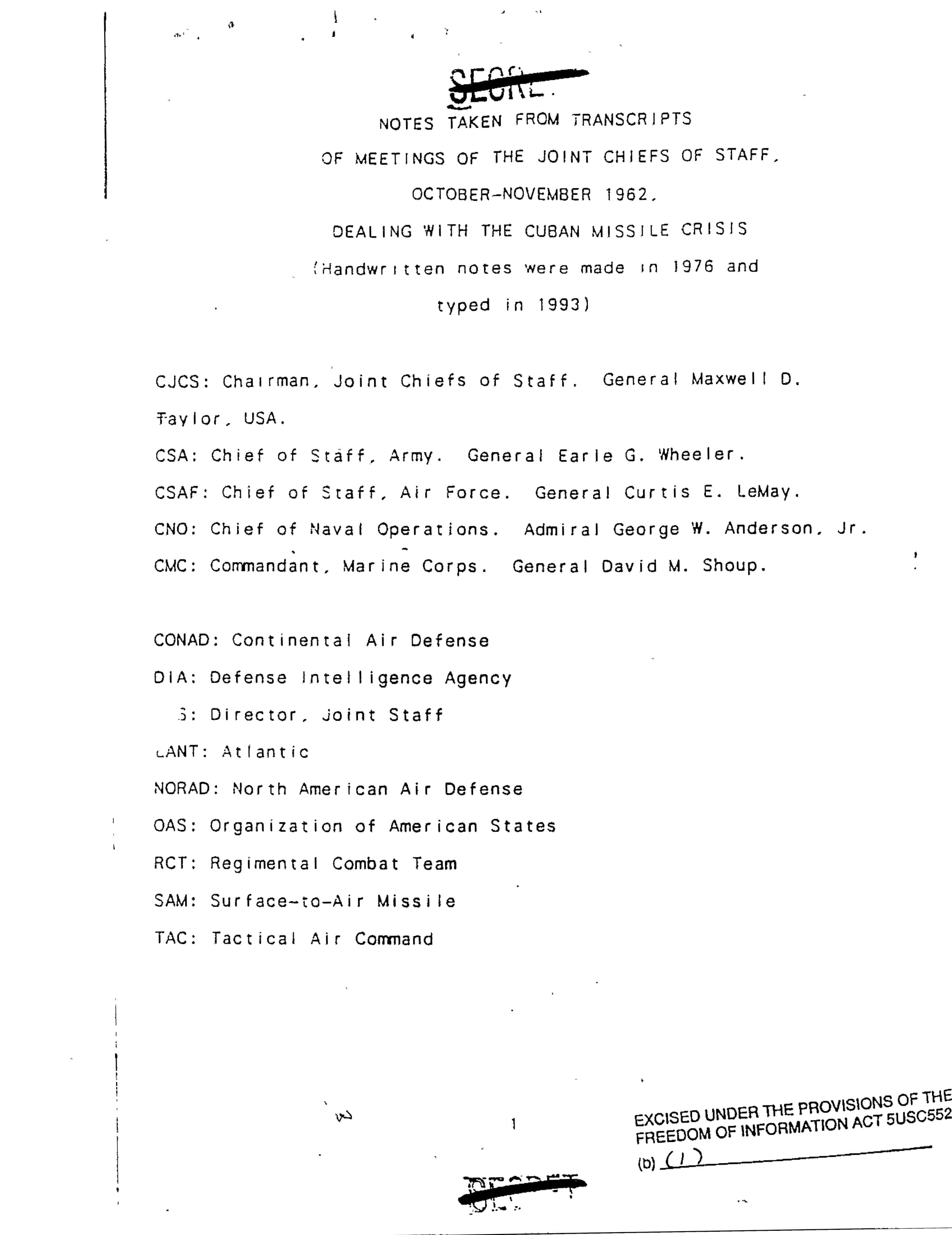

APPENDIX A: The real Joint Chiefs of Staff meeting on October 27, 1962

Shown below are authentic notes summarizing the deliberations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff on October 27, 1962 ("Black Saturday"). A PDF file of the same five pages is embedded immediately below. Additional information giving context to these notes is available on the website of the National Security Archive at George Washington University, here.

The notes refer to OPLAN 312 and OPLAN 316. OPLAN 312 was a plan for airstrikes targeting Cuban missile sites, anti-aircraft sites, airfields, and other military defenses. OPLAN 316 outlined a full-scale invasion of Cuba, incorporating extensive air strikes followed by ground operations ultimately involving up to 120,000 ground troops, with the goal of overthrowing the Castro regime and securing the island.

END NOTES

[1] President Kennedy said at an ExComm meeting on October 18, 1962, "Now the question really is what action we take which lessens the chances of a nuclear exchange, which obviously is the final failure." Although Kennedy believed that a U.S. attack on Cuba might be necessary, throughout the crisis he was more wary than most of his advisors of triggering a chain of escalation that would culminate in a nuclear exchange. For detailed discussion and documentation of the deliberations, go to the books by Dr. Sheldon Stern listed in the Selected Bibliography. For a popular-audience narrative of all dimensions of the crisis, see The Abyss: Nuclear Crisis Cuba 1962, by military historian Max Hastings.

[2] The risks of escalation to nuclear war were even greater than President Kennedy or his advisors knew, because some key pieces of information came to light only long after the crisis had passed. The U.S. knew only about the medium-range and intermediate-range nuclear missiles, but they did not know that the Soviets also had in place, at multiple sites in Cuba, dozens of cruise missiles with a range of 62-93 miles, armed with "tactical" nuclear warheads in the 5-14 kiloton range (the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima had a yield of about 15 kilotons). Unknown to the U.S., Soviet forces had moved such missiles to within range of the U.S. military base at Guantanamo Bay, on the eastern tip of Cuba, which had already been reinforced with about 5,500 U.S. Marines. In the event of an invasion, there is a substantial likelihood that tactical nuclear missiles would have been used against the base. Additionally, tactical nuclear cruise missiles would likely have targeted U.S. ships and landing forces during an invasion. Any of these actions by the Soviets would likely have triggered a nuclear response from the U.S.

Also unknown to anyone on the American side, each of the four Soviet submarines that were operating in the general blockade area carried a T-5 torpedo armed with a warhead in the 10 kiloton range. According to some accounts published years later, U.S. naval forces on October 27 employed small practice depth charges and hand grenades, among other measures, to attempt to force Soviet Foxtrot submarine B-59 to the surface. This caused the three senior officers on board the submarine to fear that war might have broken out, and to debate launching their T-5 at nearby Navy ships. After learning of this decades later, Robert McNamara commented in 2002, “We came very, very close [to nuclear war], closer than we knew at the time.”

[3] The Abyss: Nuclear Crisis Cuba 1962, by Max Hastings, p. 423, and The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy 1961-1964, by Walter S. Poole, p. 181.

[4] The Economics and Political Strategy Division (EPSD) at the Institute for Defense Analyses was one of the IDA's six major divisions, accounting for 7% of IDA's grant funding in 1964. The Economics Group, headed by Malmgren in 1964, was a subdivision of the EPSD, and therefore likely accounted for only a few percent of the total IDA budget. Activities of the Institute for Defense Analyses 1961-1964, IDA, April 22, 1964.

[5] Sheldon M. Stern, Ph.D., was historian at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library from 1977-2000. He is the author of Averting 'The Final Failure': John F. Kennedy and the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis Meetings (2003), The Week the World Stood Still (2005), and The Cuban Missile Crisis in American Memory: Myths Versus Reality (2012), as well as numerous articles and papers on the subject.

[6] Curtis LeMay is one of my least favorite figures in American military history. But although many find much to dislike in LeMay's value system and personality, this provides no justification for imputing to him actions that he never took, much less unsubstantiated allegations of criminal and treasonous activity. Harald Malmgren's eldest daughter, Pippa Malmgren, has suggested in several writings during 2025 that she believes that General LeMay may have master-minded the assassination of President Kennedy, motivated at least in part by Kennedy's purported thinking regarding extraterrestrial visitors. This theory has also been advanced by Australian writer Geoff Cruickshank. In a post on X on April 22, 2025, Jesse Michels wrote, "He [Harald Malmgren] says that JFK’s desire to collaborate with the Soviets on UFOs, space exploration and denuclearization were core parts of the impetus to assassinate him." I asked Larry Hancock, a member of the board of the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies and author of several books about the Kennedy assassination, about the idea that LeMay was involved with the JFK assassination; he replied that he has seen "no specific evidence" to support the claim. (email to author, May 19, 2025)

[7] President Kennedy was getting dressed for church when he received the news about the Soviet radio broadcast of the Khrushchev letter. He told his personal assistant, David Powers, "I feel like a new man now. Do you realize that we had an air strike all arranged for Tuesday? Thank God it's all over." (One Minute to Midnight, by Michael Dobbs, p. 334, citing Johnny, We Hardly Knew Ye: Memories of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, by Kenneth P. O'Donnell and David F. Powers, 1972, p. 341.)

[8] Harald Malmgren displayed ignorance regarding key facts about the historical settings in which he placed various of his tall tales. Perhaps he was lazy in his lies because he had become accustomed to uncritical listeners. As one example, consider Malmgren's 2024-25 story in which he investigated on behalf of President Kennedy, Secretary of Defense McNamara, and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, a purported nonhuman UFO knocked down by the Bluegill Triple Prime nuclear test of October 26, 1962. Malmgren claimed that he had oversight responsibilities over this nuclear test as part of an assignment (fictional) from McNamara to develop a plan for defense against nuclear ballistic missiles. ("My father, Ambassador Harald Malmgren, had overseen that particular missile test," affirmed daughter Pippa Malmgren.) Malmgren has described the Bluegill Triple Prime event as involving the actual shootdown of an incoming missile. ("You have videos of taking down this incoming missile with a specially enhanced x-ray projection system," he said, in one example.) But in the real Bluegill Triple Prime test, there was no shootdown of an incoming missile. The test involved a high-altitude detonation of a warhead that was itself designed to produce enhanced x-rays, while monitored by many instruments and cameras, an exercise intended in part to inform possible future development of ballistic missile defense systems. In short, Malmgren was fundamentally confused about the basic design of a nuclear test for which he claimed to have exercised White House-level oversight, and that he claimed to have extensively investigated after the fact on behalf of Secretary McNamara and President Kennedy.

In January 2025, Harald Malmgren offered an inaccurate description of the Bluegill Triple Prime nuclear test of October 26, 1962, over which he falsely claimed to have exercised oversight authority and to have subsequently investigated from the Kennedy White House. Fair Use under 17 U.S. Code § 107 for noncommercial purposes of investigative journalism, scientific research and debate, education, commentary, and criticism.

[9] After Khrushchev's letter promising withdrawal of the missiles was broadcast on the morning of October 28, 1962, LeMay "did not trouble to hide his rage that the USAF's beautiful programme of air strikes, designed to devastate Cuba, at a stroke appeared redundant," wrote military historian Max Hastings (The Abyss, p. 430). Joint Chiefs official historian Walter Poole wrote, "LeMay feared that the Soviets might carry out a charade of withdrawal while keeping some weapons in Cuba." (page 182)

In Averting 'The Final Failure', Sheldon Stern wrote:

The Joint Chiefs remained extremely suspicious, warning the President that the announcement was an effort "to delay direct action by the United States while preparing the ground for diplomatic blackmail." They also urged JFK to order sweeping air strikes in Cuba in 24 hours, followed by an invasion, unless irrefutable evidence proved that the missile sites were being dismantled. General Taylor dissented, but agreed to transmit the recommendation to the Secretary of Defense....General LeMay denounced the agreement as "the greatest defeat in our history" and banged the table demanding, "We should invade today!" McNamara later recalled that JFK was so stunned by LeMay's outburst that he could only stutter in response. (p. 385)

[10] Historian Sheldon Stern does not think that it would have taken even years for such a clash to have become widely known. "If anything like that had happened, it could hardly have remained secret very long in leak-obsessed Washington," he observed. (email to author)

[11] "After McNamara killed the B-70 and a host of other Air Force weapons, and then stopped building Minutemen after reaching 1,000 missiles, LeMay would often ominously inquire of his Air Force friends, 'I ask you: would things be much worse if Khrushchev were Secretary of Defense?'" – The Wizards of Armageddon, by Fred Kaplan (1983), p. 256.

[12] McNamara said of LeMay, "Kennedy was trying to keep us out of war. I was trying to help him keep us out of war. And General Curtis LeMay, whom I served under as a matter of fact in World War II, was saying 'Let's go in, let's totally destroy Cuba.'" – “Empathize with Your Enemy,” The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, directed by Errol Morris, 2003.

[13] The 2017 Irish Times article quoted Harald Malmgren directly as stating, "I was a superstar academic in those days [circa 1961]. I was like being somebody who was the number one draft for the NFA." However, "NFA" was probably a stenographic error or transcription error by the newspaper writer. In the January 2025 Jesse Michels interview, Malmgren said "there was a bidding war, like an NBA or National Football League bidding for graduates..." (at 33:52)

[14] Jonathan Swift, The Examiner No. 14, November 9, 1710. Readers may be more familiar with the similar observation often attributed to Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens): "A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes." To my disappointment, I found that Mark Twain never actually wrote that; it seems somebody just made up that attribution.

[15] On his April 2025 Need to Know podcast, Ross Coulthart identified Harald Malmgren as "one of the key junior staffers in the JFK White House." As I showed in my May 20, 2025 article examining Malmgren's professional history in great detail, Malmgren was never any kind of staffer in the JFK White House. The only basis I found for a formal Malmgren connection even with the Kennedy Administration was a by-the-hour economist-consultant gig for the State Department, which Malmgren began just one month before the end of the Kennedy Administration. Malmgren didn't even bother to mention this trifle on the employment history he provided for FBI use on August 25, 1971. Malmgren did not become a full-time federal employee until October, 1964.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Herald Malmgren: Real-world history versus grandiose fantasy," by Douglas Dean Johnson, published on Mirador on May 20, 2025. This is my main article documenting the real career of Harald Malmgren, and examining ten of his specific claims in light of his documented history. The article you are reading is a sidebar to the main Malmgren article.

Dobbs, Michael. One Minute to Midnight. Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War. Knopf/Vintage Books, 2008-2009.

Hastings, Max. The Abyss: Nuclear Crisis Cuba 1962. Harper Collins, 2022. I recommend this book to any reader seeking a single volume on the Cuban Missile Crisis. The author, a well-regarded military historian, presents a crisp and insightful narrative. The book includes many helpful maps, diagrams, and photographs.

Kaplan, Fred. The Wizards of Armageddon. Simon and Schuster, 1983. Much information about Robert McNamara, the real "whiz kids," Herman Kahn and other nuclear strategists, and other matters pertaining to nuclear war planning.

Keeney, L. Douglas. 15 Minutes: General Curtis LeMay and the Countdown to Nuclear Annihilation. St. Martin's Press, 2011.

Poole, Walter S. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy, Volume VIII, 1961-1964, 2011.

Stern, Sheldon M. Averting 'The Final Failure': John F. Kennedy and the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis Meetings. Stanford University Press, 2003. A highly regarded scholarly work on the progression of the Cuban Missile Crisis as revealed by the declassified ExComm recordings.

Stern, Sheldon M. The Week the World Stood Still: Inside the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis. Stanford University Press, 2005. A more condensed, general-audience treatment of the history as revealed by the ExComm recordings.

Stern, Sheldon M. The Cuban Missile Crisis in American Memory: Myths versus Reality. Stanford University Press, 2012. Stern examines widespread misconceptions about the Cuban Missile Crisis, some of them perpetrated by Robert Kennedy's book 13 Days and the 2000 movie based on that book, and by other Kennedy Administration figures who remained committed to narratives incompatible with the recordings.

CHRONOLOGICAL LOG OF REVISIONS AFTER INITIAL PUBLICATION

(1) June 10, 2025: Added quote from Warren Kozak, author of a biography of General Curtis LeMay.