Crash Story File: Reme Baca (AKA Ray Baca)-- Fantasy Kingmaker, Fabricator of Tall Tales

By Douglas Dean Johnson

Original publication: May 1, 2023. Any later updates and revisions are noted in a log that appears at the end of the article.

@ddeanjohnson on X/Twitter

You are in the Crash Story Files, a series of investigative reports examining claims that a UFO crashed and was recovered near San Antonio, New Mexico, in August 1945. To go back to the Crash Story hub story and index, click here.

Was Remigio (Reme) Baca (“Ray Baca”), who claimed to be an eyewitness to a UFO crash in New Mexico in 1945, later a political heavyweight in Washington State, responsible for the election of Dixy Lee Ray as governor in 1976? Was Baca ever a close associate of Governor Ray and a member of the governor’s “executive staff”?

If you just want the bottom line, my investigation found that the answer to both of those questions is “no.”

Yet, both of the authors of Trinity: The Best-Kept Secret, Jacques Vallee and Paola Harris, in various interviews have asserted that those claims by Baca are true. Often, they couple such assertions with a story about how Governor Dixy Lee Ray showed Baca an ultra-secret file about the very same 1945 UFO crash that Baca had witnessed when he was six years old.

Of course, all of these claims originated with Baca himself. Harris and Vallee were merely repeating things Baca had said, with their own commentary added.

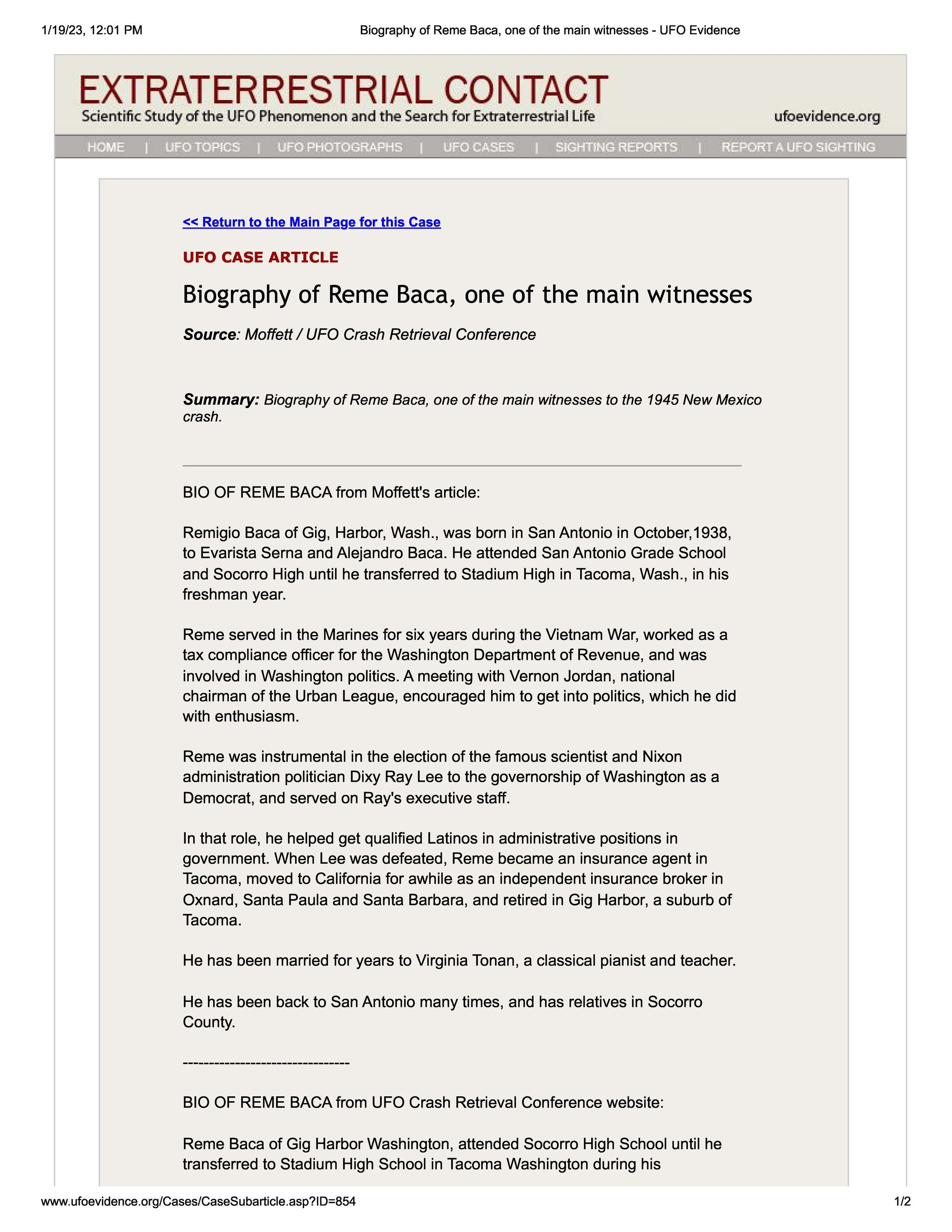

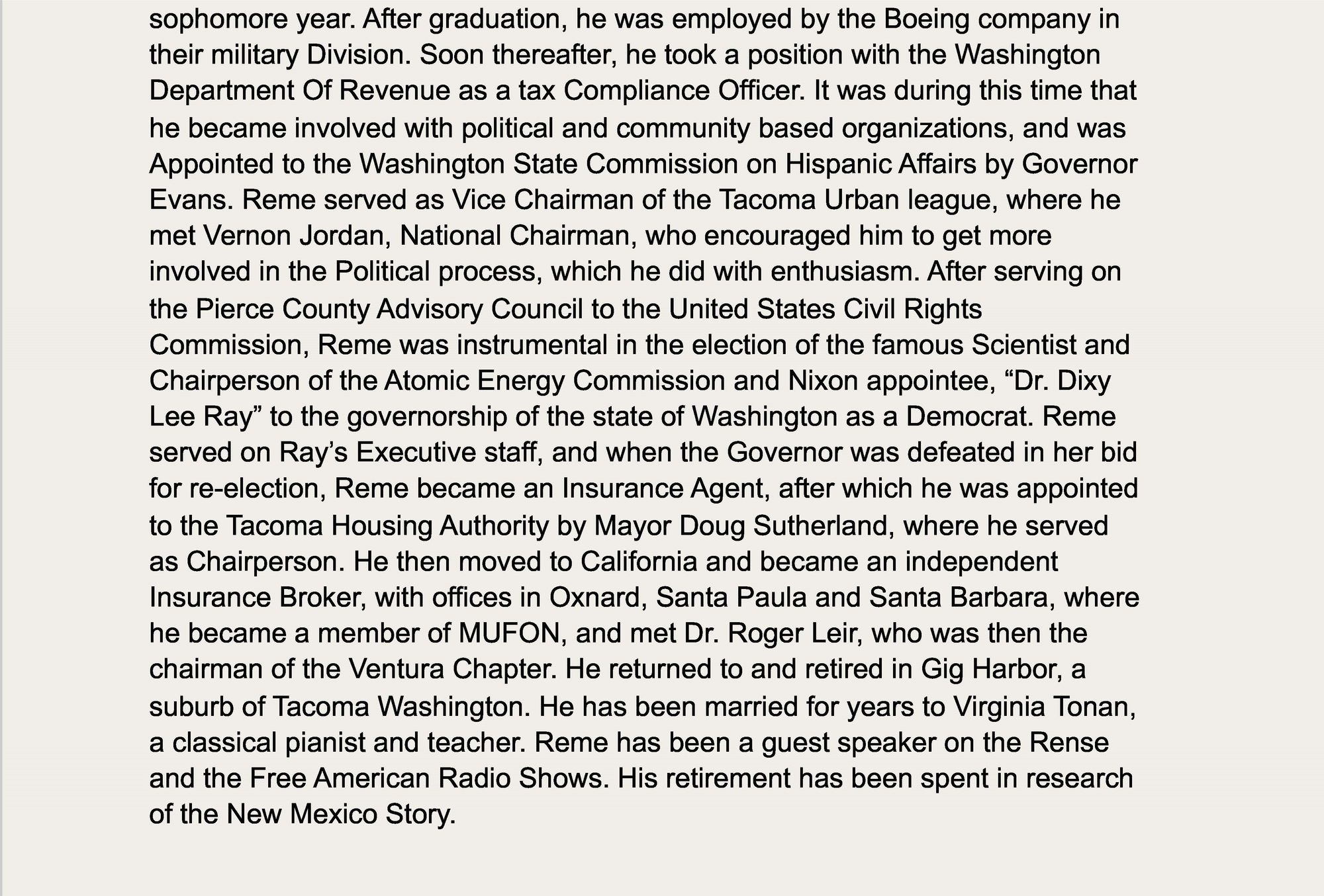

Some other amplifiers of the Trinity story have accepted such representations at face value. Ben Moffett, the writer for the Mountain Mail who was the first to write up the Baca-Padilla UFO crash story in 2003, wrote that “Reme was instrumental in the election [of Governor Ray]...and served on Ray’s executive staff.” However, in 2015 Moffett wrote that in his articles, he merely reported what Baca and Padilla had told him.

Josh Boshwell and Chris Sharp reported in the UK Daily Mail (December 29, 2022), “Baca, who died in 2013, became a US Marine and later a senior staffer for Washington Governor Dixy Lee Ray.”

I discuss the absurdity of the secret-file story in Crash Story File: The “Secret File” of Governor Dixy Lee Ray. In this article, I examine the underlying claims that Baca was a political big-shot in Washington State and a member of Governor Ray’s inner circle.

I found that Baca was a pretty marginal figure in the Washington State political world, and a fairly minor volunteer player in the 1976 political campaign of Dixy Lee Ray for governor of Washington State. Baca, a local Hispanic activist in Tacoma, was one of two people designated as volunteer coordinators to seek support for Ray in the Hispanic community. As discussed below, Baca did apparently reap some rather minor rewards for his support for Ray’s campaign, mainly a promotion in the state unemployment-benefits agency in which he was already employed, and a nomination to an unpaid 11-member advisory body called the Mexican-American Affairs Commission.

But Baca was never a member of the governor’s executive staff, or anything close to it.

To support his greatly inflated claims decades later, Baca engaged in wholesale plagiarism. In Baca's self-published 2011 book, Born on the Edge of Ground Zero, he adopted wholesale, nearly verbatim, multiple pages of text from a book written by a man who really was a key personal and political associate of Dixy Lee Ray and later a top aide to Governor Ray: Louis R. Guzzo.

Elsewhere in his book, Baca embraced the term “kingmaker” with regard to his role in the 1976 gubernatorial election.

DIGGING INTO THE RECORDS

In my research into Reme Baca’s place in the Washington State political world of the 1970s, I benefited greatly from the efforts of the Research Services staff of the Washington State Archives, within the Office of the Secretary of State, executing requests that I filed under the state’s public-records law.

In addition, I received much valuable assistance from the archivists at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, housed at Stanford University, which holds the Dixy Lee Ray Papers. This is a collection of records retained by Dixy Lee Ray during all of her career stages, including her term as governor. The total collection is held in more than 200 boxes, occupying 119 linear feet.

BACA’s “KINGMAKER” CLAIM

This much is true: Baca moved to Tacoma, Washington, in 1955, when Baca was age 16. He apparently graduated from Stadium High School in Tacoma.

In Baca’s 2011 book, in a passage dealing with an influential teacher (on page 19), Baca said that the teacher lending him books over the summer was “a fact that I am sure enabled me to become the first college graduate in my family.” However, no source I found, including Baca’s obituary, contains any evidence that he attended any college, much less graduated.

According to Ben Moffett’s short bio of Baca, published in 2003 and based on Baca’s statements, “Reme served in the Marines for six years during the Vietnam War.” That statement was technically accurate. However, some readers might misunderstand it to mean that Baca served in the Marines in Vietnam. I obtained some documents pertaining to Baca’s military record. They show that he enlisted in a United States Marine Corps National Guard unit based in Tacoma in 1957, and was part of that organization for six years, until 1963. In that era, few National Guard units were mobilized for combat service. Baca’s service was entirely on the home front. His record shows a number of "not satisfactorily completed" and "inactivity" entries for 1958 and later, but I am unable to interpret the significance of those entries. In any event, Baca was honorably discharged as a private first class effective January 16, 1963.

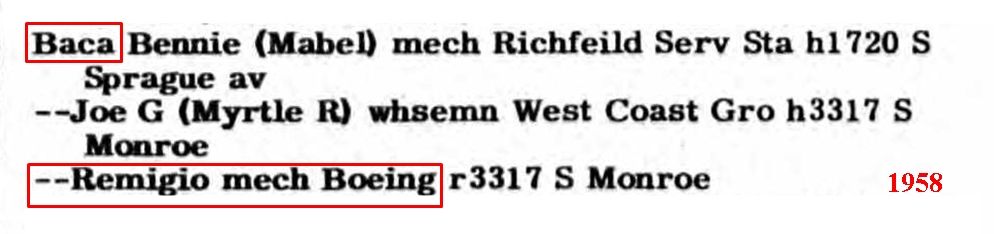

Baca was employed by the Boeing Company as a mechanic in 1958. He later said it was in the “military division.” (“...where he had worked on all types of military and commercial air craft, including Air force One.” Born on the Edge of Ground Zero, p. 72.)

Baca married Virginia Tonan in 1959; they had three children.

Baca later (apparently during the 1960s) earned his living “with the Washington Department of Revenue as a tax Compliance Officer,” according to the “Baca vita” (2005).

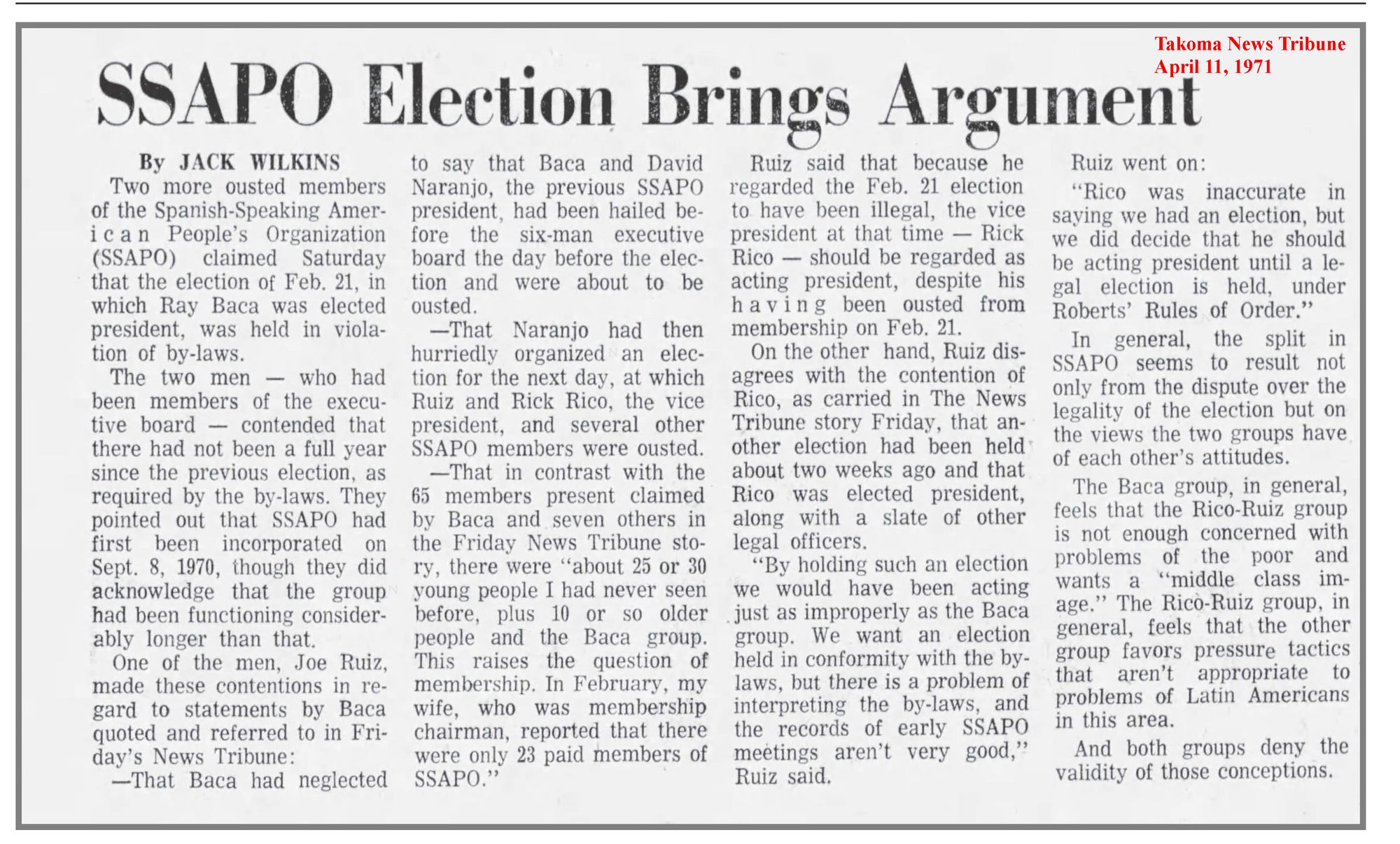

While living in Tacoma in the 1970s, Baca also became an activist of sorts in the Hispanic community. However, he was not such a prominent figure that he left much of a trail in the news media. It appears that at times Baca was a man who engendered some contention within the Hispanic community, although the details are obscure.

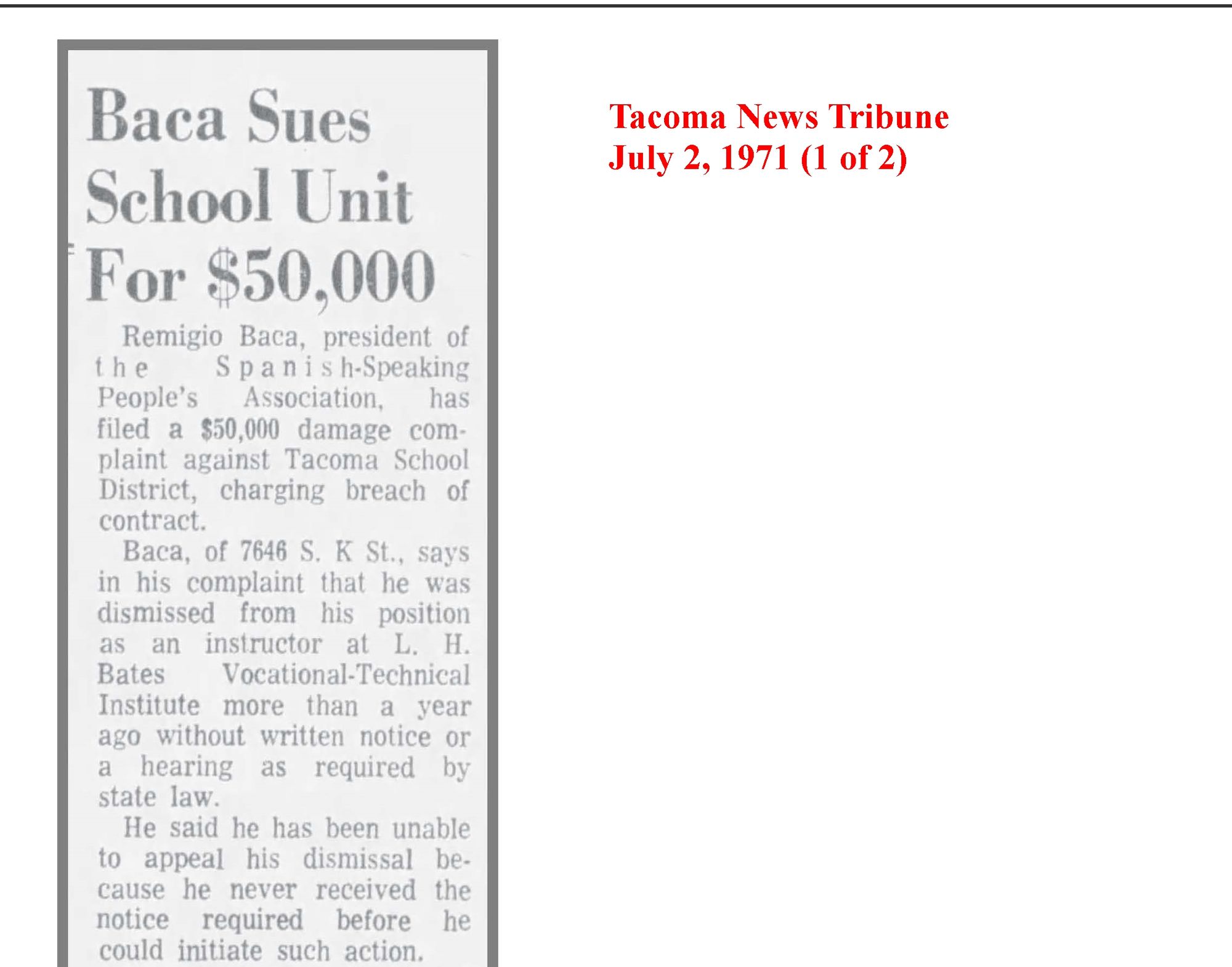

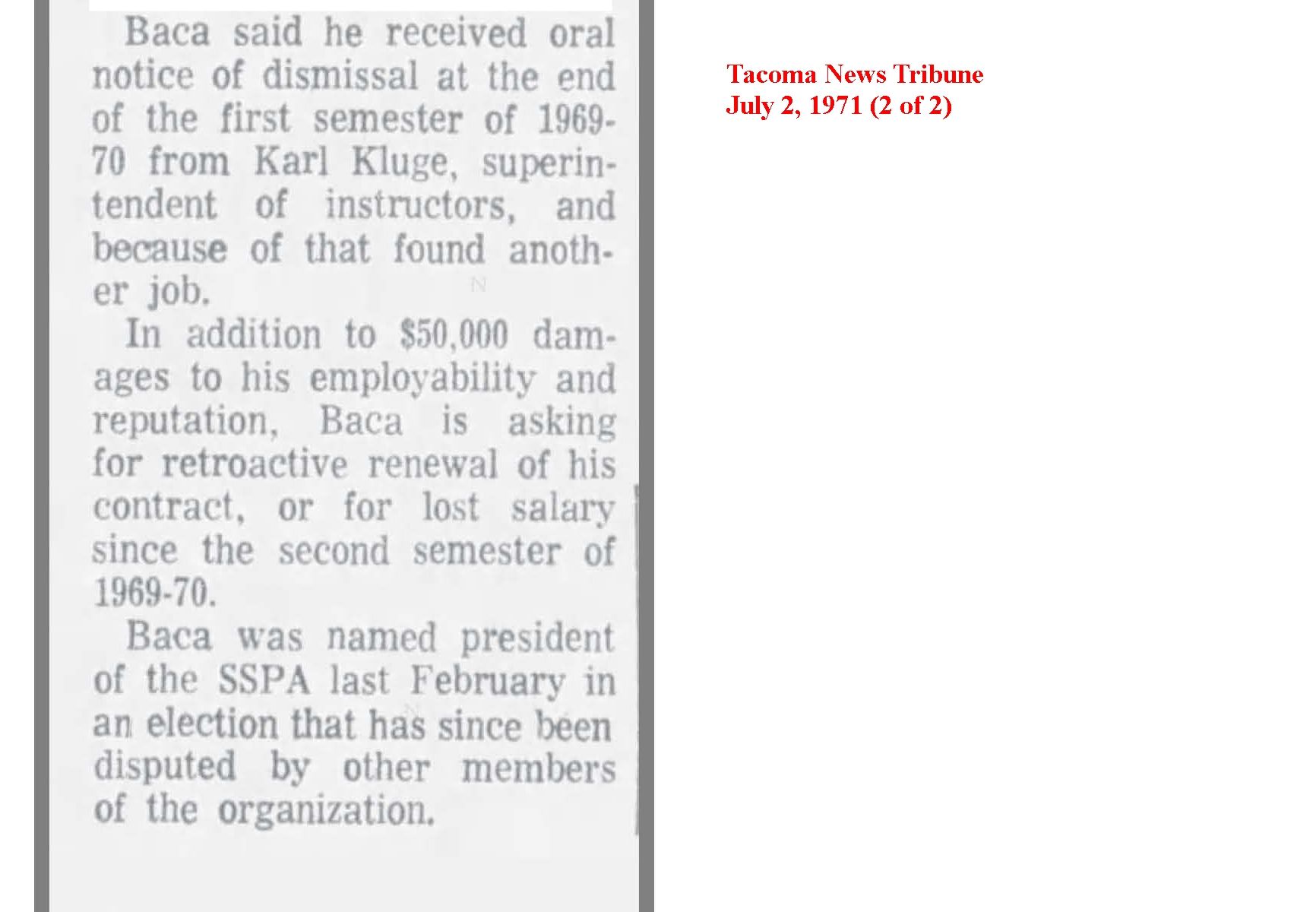

For example, a report in the July 2, 1971 issue of the News Tribune, a Tacoma newspaper, identified Baca as “president of the Spanish-Speaking Citizens Association.” The article said, “Baca was named president of the SSPA last February in an election that has since been disputed by other members of the organization.” The same article said that Baca had filed a $50,000 lawsuit against the Tacoma School District, alleging that he has been dismissed as an instructor at the L.H. Bates Vocational-Technical Institute “without written notice or a hearing as required by state law.”

However, Baca’s stature in the Tacoma Hispanic community became sufficient that in 1976, Governor Dan Evans (a Republican who served as governor from 1965-1977) nominated Baca to an unpaid seat on an 11-member advisory panel called the Mexican-American Affairs Commission, for a term that was to end July 1, 1979. A short news article in the News Tribune of August 13, 1975, reported on the appointment of “Ray Baca" (as he was then known), who was identified as “an employment service specialist with the State Employment Security Department since 1970.” That was the state agency responsible administering unemployment benefits.

In his 2011 book, Born on the Edge of Ground Zero, Baca devoted only part of one sentence to this nomination by Governor Evans (a nomination that was never confirmed by the Washington State Senate), the significance of which apparently paled in Baca’s mind next to the highpoint of his pre-1976 political activity:

I was asked by the Office of Governor Evans to chair a welcoming committee for President Ford and First Lady Betty. [Such events usually have multiple chairs.] The encourage included First Lady Betty Ford and her friend Za Za Gabor, Conrad Hilton’s former spouse, and many republican officials from throughout the United States. I sat at the table with First Lady Betty Ford and her friend Za Za Gabor at the function, it was an expectation that I did not think I would achieve. (Born on the Edge of Ground Zero, pp. 58-59)

BACA’S ROLE IN THE ELECTION OF DIXY LEE RAY

Although Baca had previously been a supporter of Governor Evans, a Republican, after Evans announced that he would not seek re-election and Dixy Lee Ray began her 1976 campaign for governor, running as a Democrat, Baca switched his party allegiance and supported Ray. (Regarding the previous work of Dixy Lee Ray in the federal government, I refer the reader to Crash Story File: The 'Secret File' of Governor Dixy Lee Ray.)

I see no reason to doubt that Baca did whatever he could to mobilize Hispanic support for Ray during the 1976 primary and general election campaigns. However, I searched extensively and found nothing to indicate that those efforts were very important to Ray’s ultimate success. In searching multiple newspaper databases that included the Tacoma newspaper, I found no reference at all to Ray Baca/Reme Baca in association with Ray's 1976 campaign.

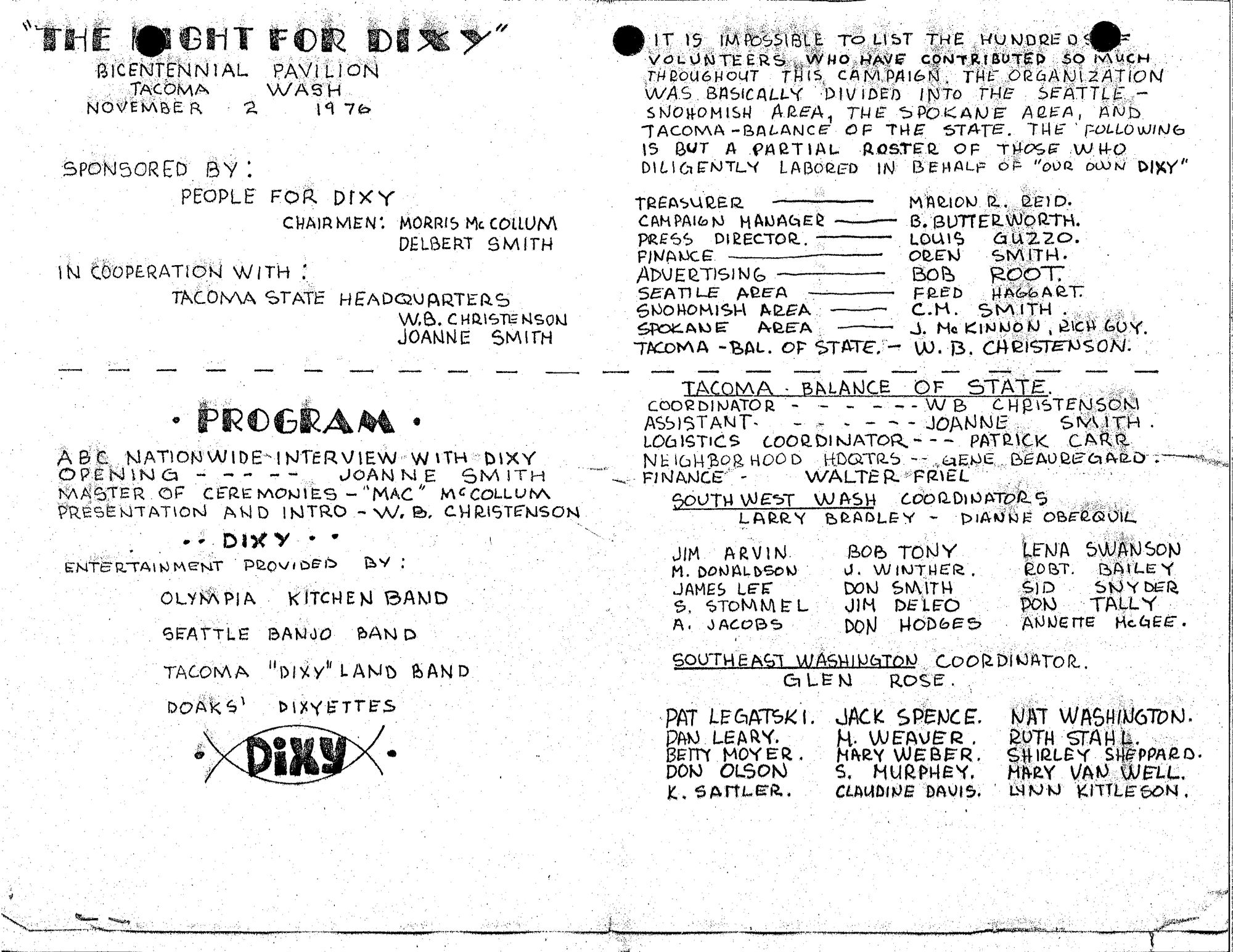

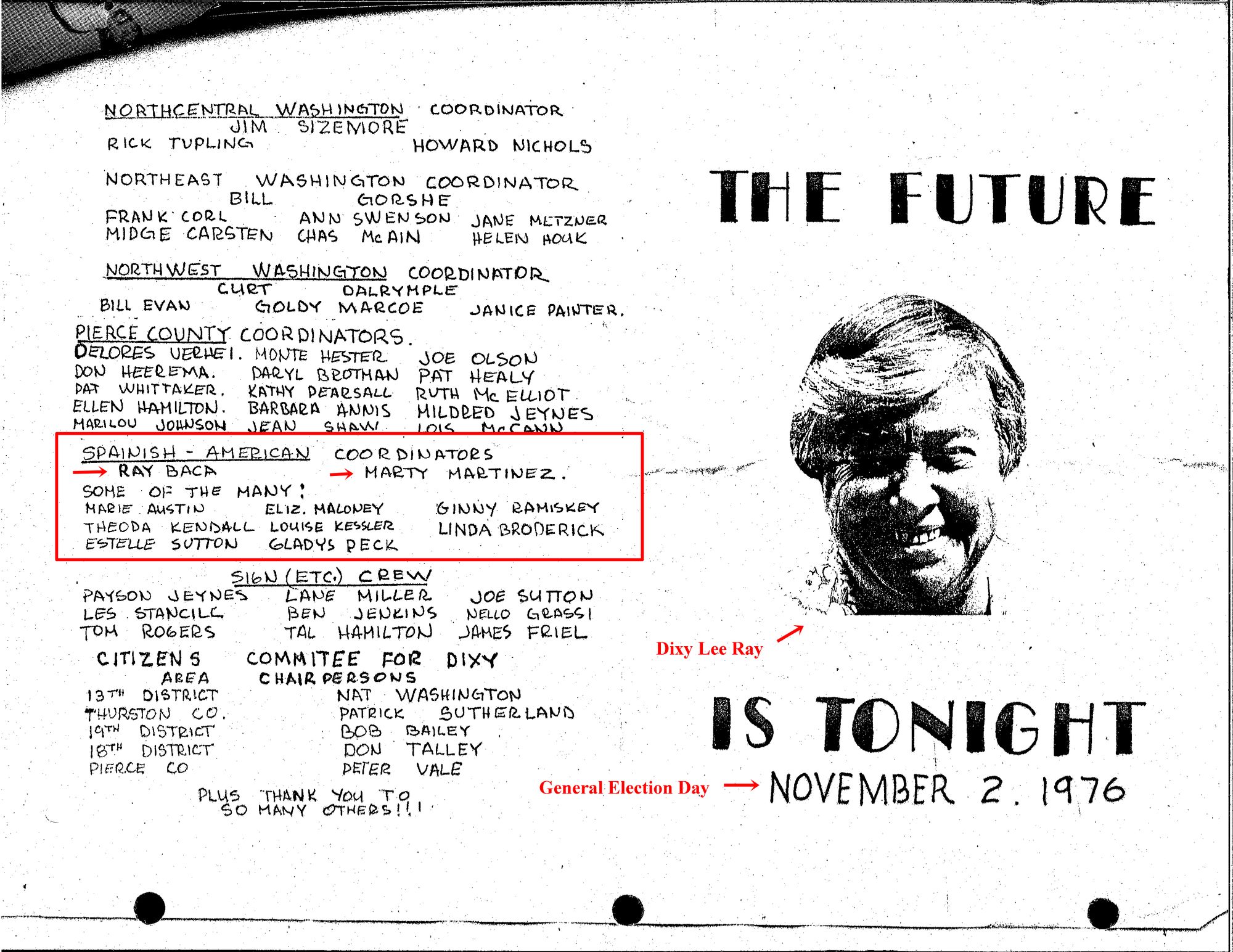

However, among the documents that I obtained from the Washington State Archives was a flyer produced by a campaign committee, “People for Dixy,” and by the Tacoma State Headquarters for the Ray campaign, promoting an election-night event (November 2, 1976). The flyer, embedded below, lists key staff (both paid and volunteer) for the entire statewide Dixy Lee Ray gubernatorial campaign. The name of “Ray Baca” does not appear among the rosters of the top statewide campaign personnel. However, “Ray Baca” is listed as one of two “Spanish-American Coordinators.” (See the red highlighting that I have placed on the image.)

Louis R. Guzzo, a longtime friend and associate of Dixy Lee Ray who was Ray’s closest advisor during her 1976 campaign, published an admiring biography of Ray in early 1980 as she began her unsuccessful campaign for re-election. While the book devoted many pages to Dixy Lee Ray's 1976 campaign, Baca’s name did not appear in Guzzo’s book.

BACA’S ROLE IN GOVERNOR RAY’S ADMINISTRATION

On January 12, 1977, Dixy Lee Ray was sworn in as governor of Washington State. Ray had never held elective office before. According to Louis R. Guzzo, writing in 1980, “The new governor was expected to come up with more than 2,000 appointments to some 350 boards, commissions, and councils... Governor Ray delayed appointments past statutory deadline because she was not satisfied with the caliber of applicants...”

It appears that Gov. Evans’ nominations to the Mexican-American Affairs Commission (which had never been confirmed by the state Senate) were among the appointments that Governor Ray found unsatisfactory, because she withdrew 10 nominations to the commission —including the nomination of Ray Baca.

On January 21, 1977, Governor Ray’s staff produced a memo suggesting the reappointment of four previous nominees, including Ray Baca, but for whatever reasons, that did not happen.

On May 25, 1977, Governor Ray received a memo from the “Mexican American Ad Hoc Committee,” sent on the letterhead of Mariano Torres, executive director of the Washington State Commission on Mexican-American Affairs. Ray Baca was listed as one of the 19 members of this “ad hoc committee.” The memo, 13 pages long, contained detailed recommendations for increasing the presence of Hispanics in the state government, including an appointment of a "Governor's Office Staff Assistant," apparently conceived as a position that really would be part of the governor's executive staff. The memo recommended four specific names the governor should consider for such a position on her executive staff, but Ray Baca was not among the names recommended.

The Mexican-American Affairs Commission apparently turned out to be a low priority for Governor Ray, or maybe she couldn't get sufficient consensus on who to appoint– in any event, she did not actually get around to nominating anyone to the commission until April 6, 1978. Because of this long delay, the commission lacked a quorum and was unable to meet or conduct its business for about a year and a half.

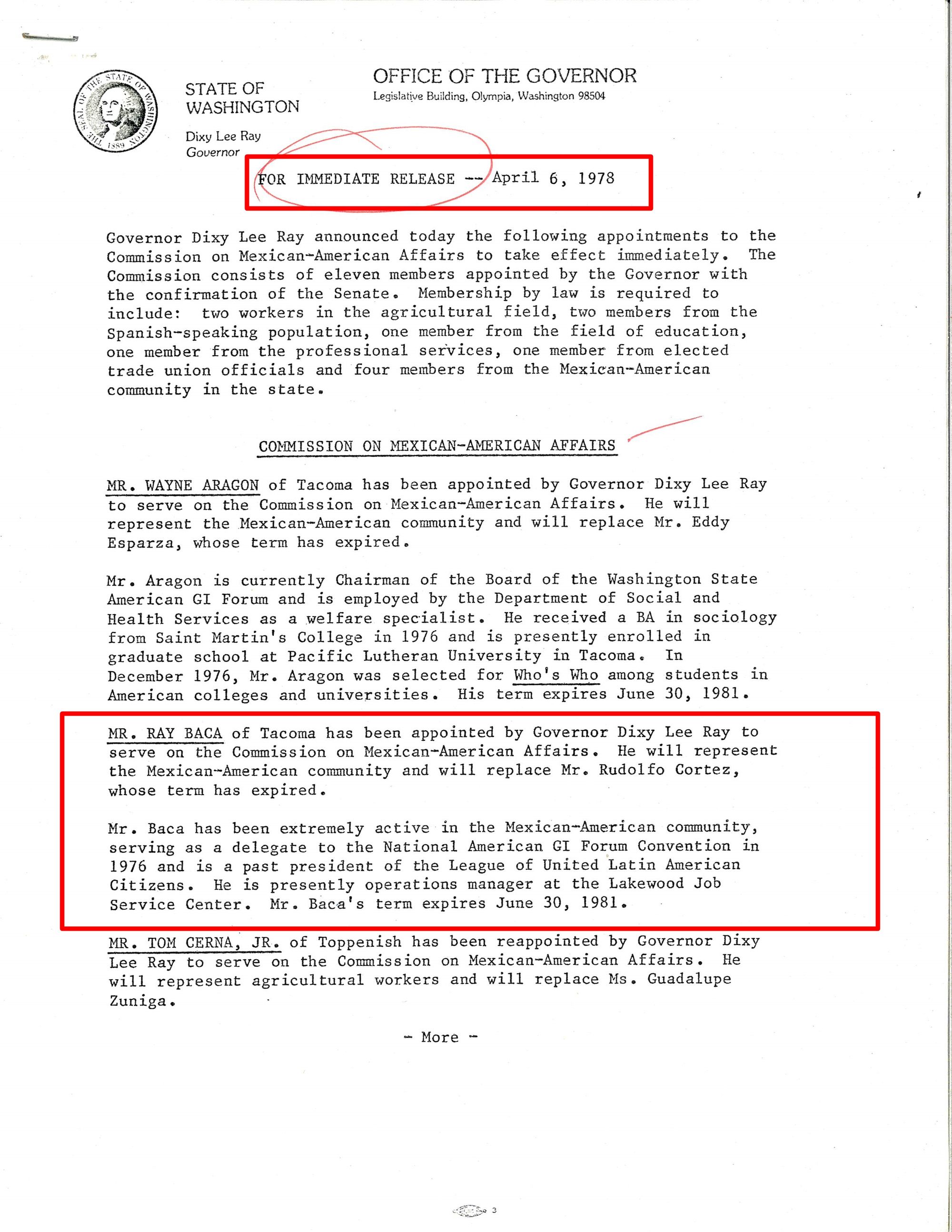

Finally, the governor's office announced 11 nominations in a press release dated April 6, 1978. Ray Baca was among the picks, nominated to one of the four seats designated by law to represent “members from the Mexican-American community in the state.” The release devoted two paragraphs to Baca, stating that he “has been extremely active in the Mexican-American community, serving as a delegate to the National American GI Forum Convention in 1976 and is a past president of the League of United Latin American Citizens. He is presenting operations manager at the Lakewood Job Service Center.”

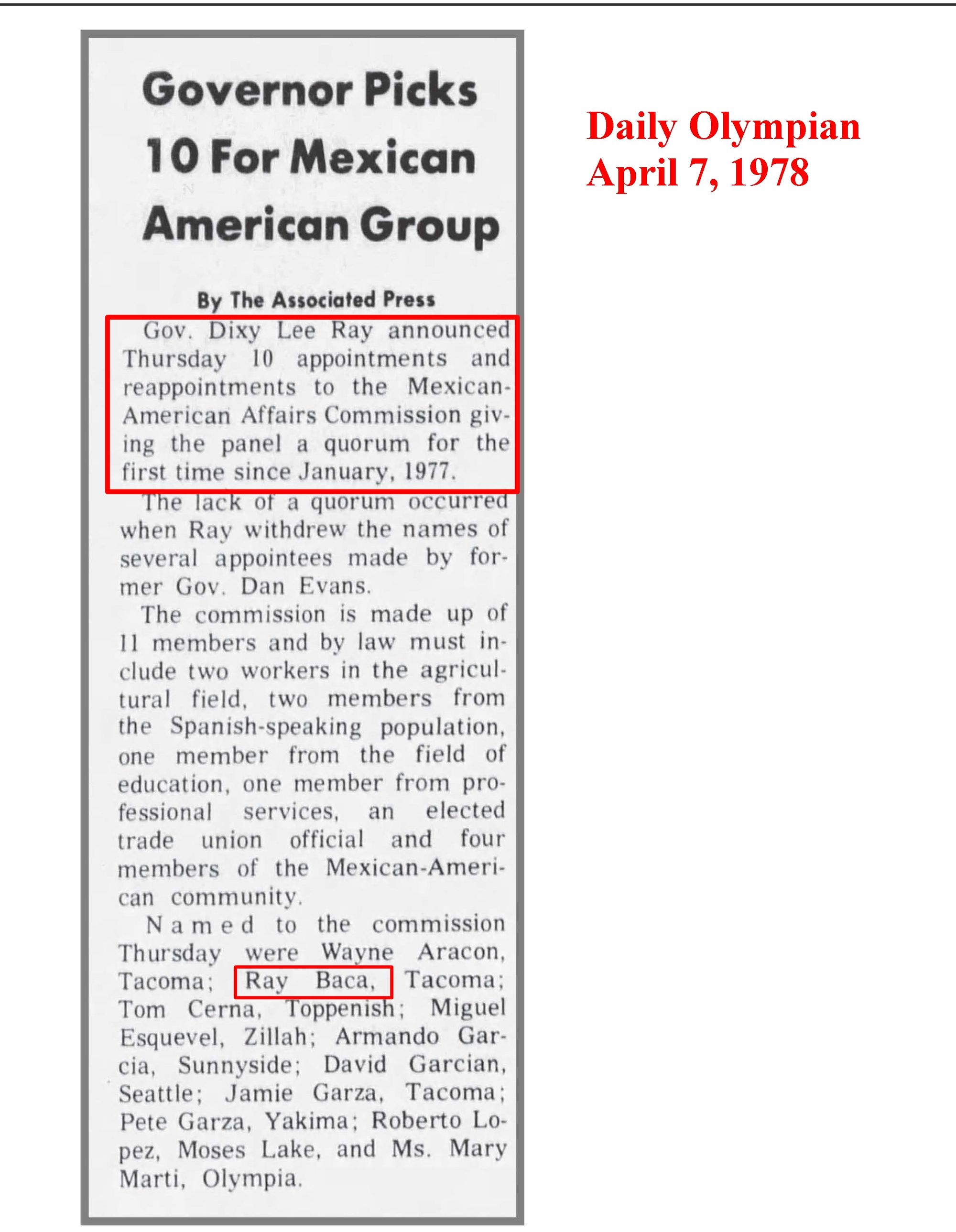

Governor Rays nominations were reported in the Daily Olympian of April 7, 1978.

BACA AND GOVERNOR RAY’S “EXECUTIVE STAFF”

Based on the documentation that I reviewed, the characterization by Paola Harris of Baca as “the head of the Hispanic community” was a substantial exaggeration, as applied to either the entire state or even to just Tacoma, but at least it was based on a nub of truth.

The same cannot be said for Baca’s claims to have been a member of Governor Ray’s “executive staff.” A governor’s executive staff would be the people who work in the office of the governor, who work under the direction of a chief of staff, and who interact directly with the governor. Baca had been characterized as a member of Governor Ray’s executive staff by Ben Moffett in 2003, in the “Baca vita” circa 2005, and by Paola Harris in various interviews. I can state with confidence that Baca never held any position remotely approaching a position on Governor Ray’s executive staff.

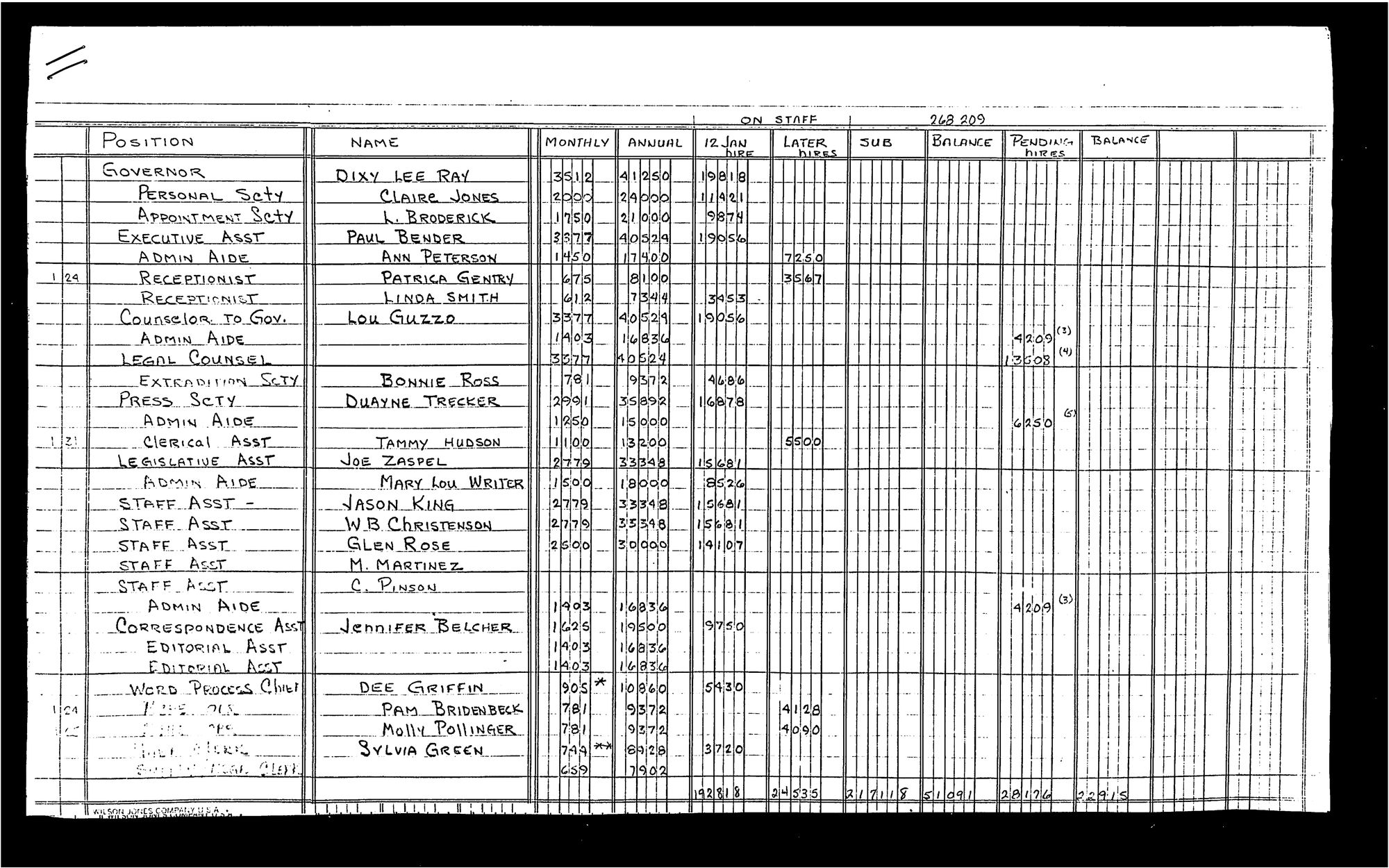

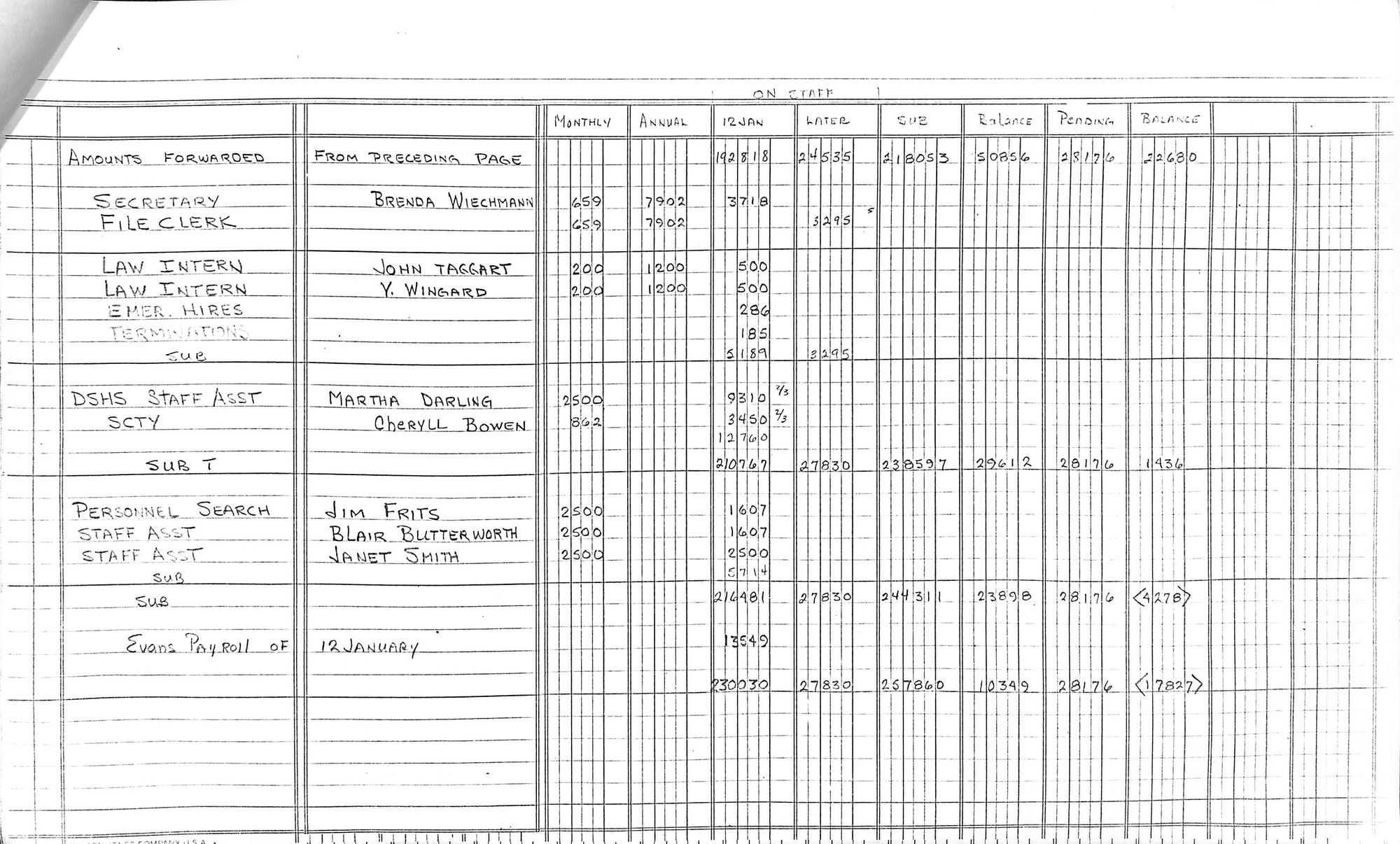

Governor Ray’s executive assistant, Paul C. Bender, wrote a memo dated February 15, 1977, “Subject: Organization of Immediate Office of Governor Ray,” to which he attached “Personnel in the Office of Governor Dixy Lee Ray,” listing 35 positions and 32 names. Ray Baca’s name did not appear.

A directory of phone numbers associated with Governor Ray and her executive staff, dated March 15, 1977, did not contain Ray Baca’s name.

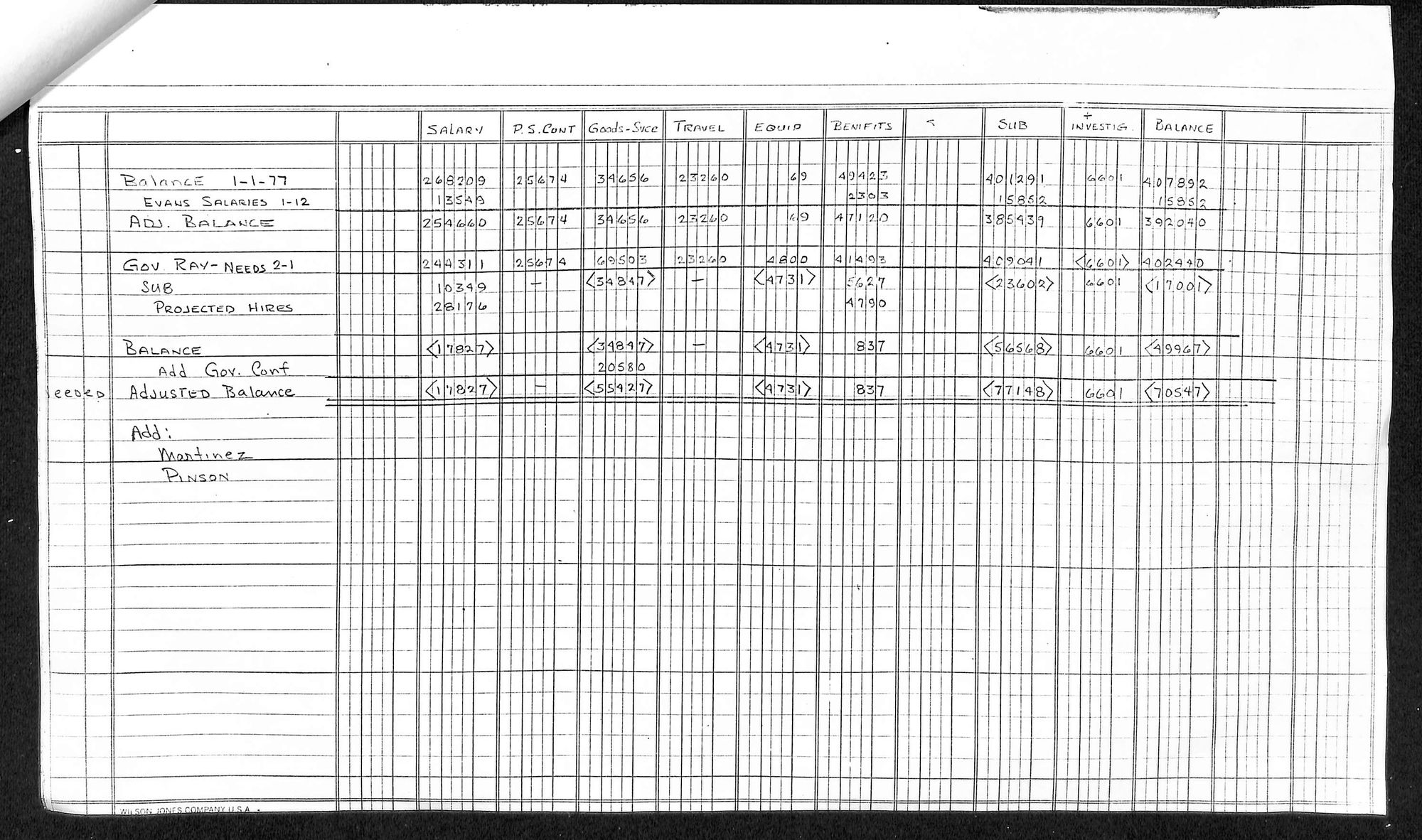

A budget document for Governor Ray’s office, found in a file of Governor Ray’s papers from 1979 held by the Hoover Institute Library & Archives, also did not list Ray Baca.

Hoover Institute archivist also reviewed some of the primary records of the operations of Governor Ray’s staff, finding no trace of Ray Baca. For example: “In the weekly 1977 executive staff/cabinet meetings, Baca was not present.... The first page of the notes of each of these meetings lists attendance, and I was not able to find Baca’s name on any of these lists.”

In addition, searches of newspaper archives that included major Washington State newspapers, found nothing related to Baca’s work during the Ray Administration, except for the notice of his re-nomination to the Mexican American Affairs Commission already shown above, and a single item related to his responsibilities with a fairly obscure state agency, as discussed in the next subsection of this article.

In summary: In places where Baca’s name should have appeared again and again, if his claim had been true, it did not appear.

BACA GETS A JOB PROMOTION

I did find evidence that Baca may have received a modest reward for his 1976 volunteer work in support of Ray’s candidacy. In mid-1978, about 18 months after Governor Ray took office, Baca received a promotion within the Employment Security Department, where he had already been employed in a minor management position at a branch office.

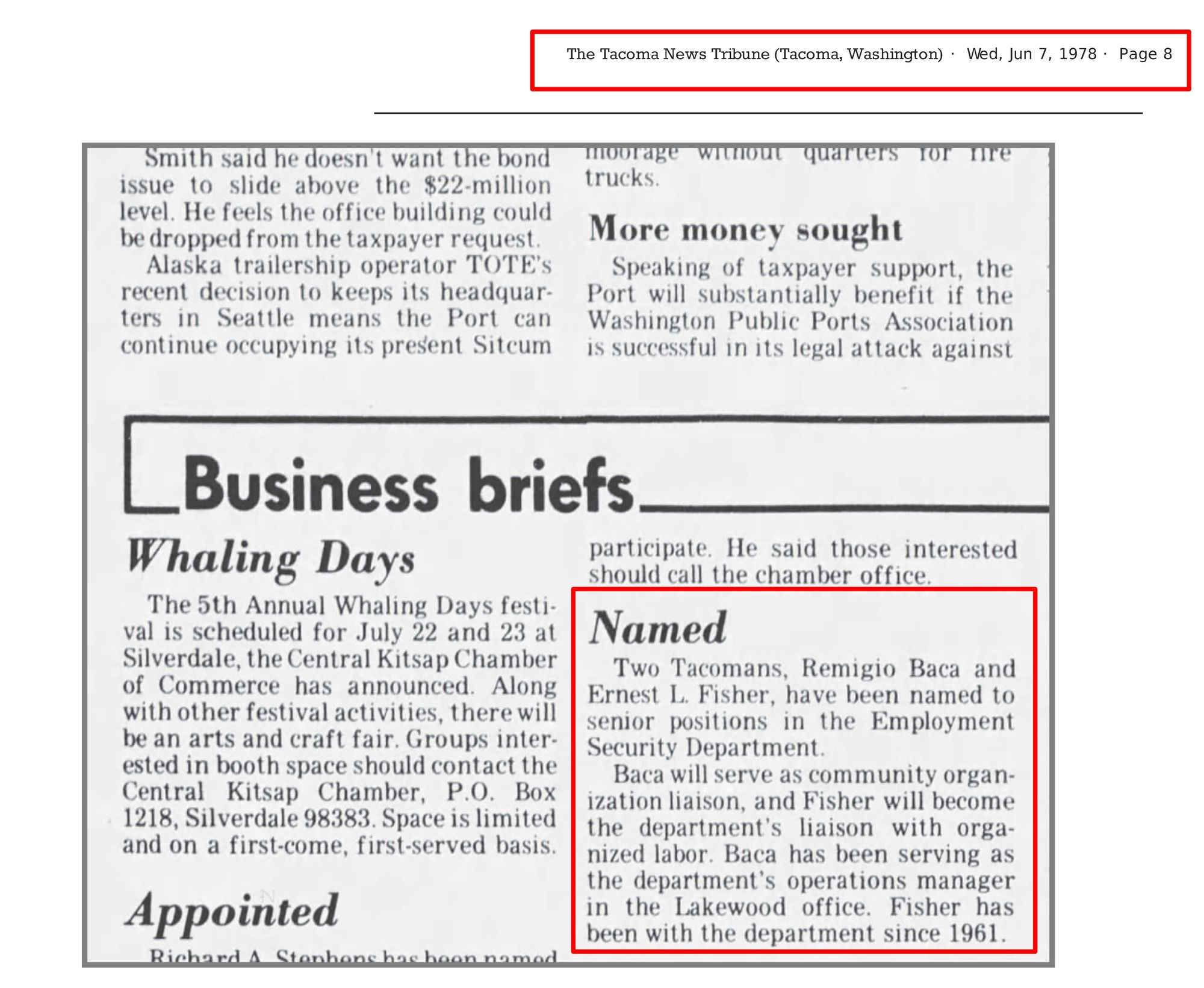

On June 7, 1978, the Tacoma News Tribune ran a very short item, probably based on a press release, that “Remigio Baca” was one of two persons “named to senior positions in the Employment Security Department” (the state agency handling unemployment benefits). “Baca will serve as community organization liaison...Baca has been serving as the department’s operations manager in the Lakewood office.”

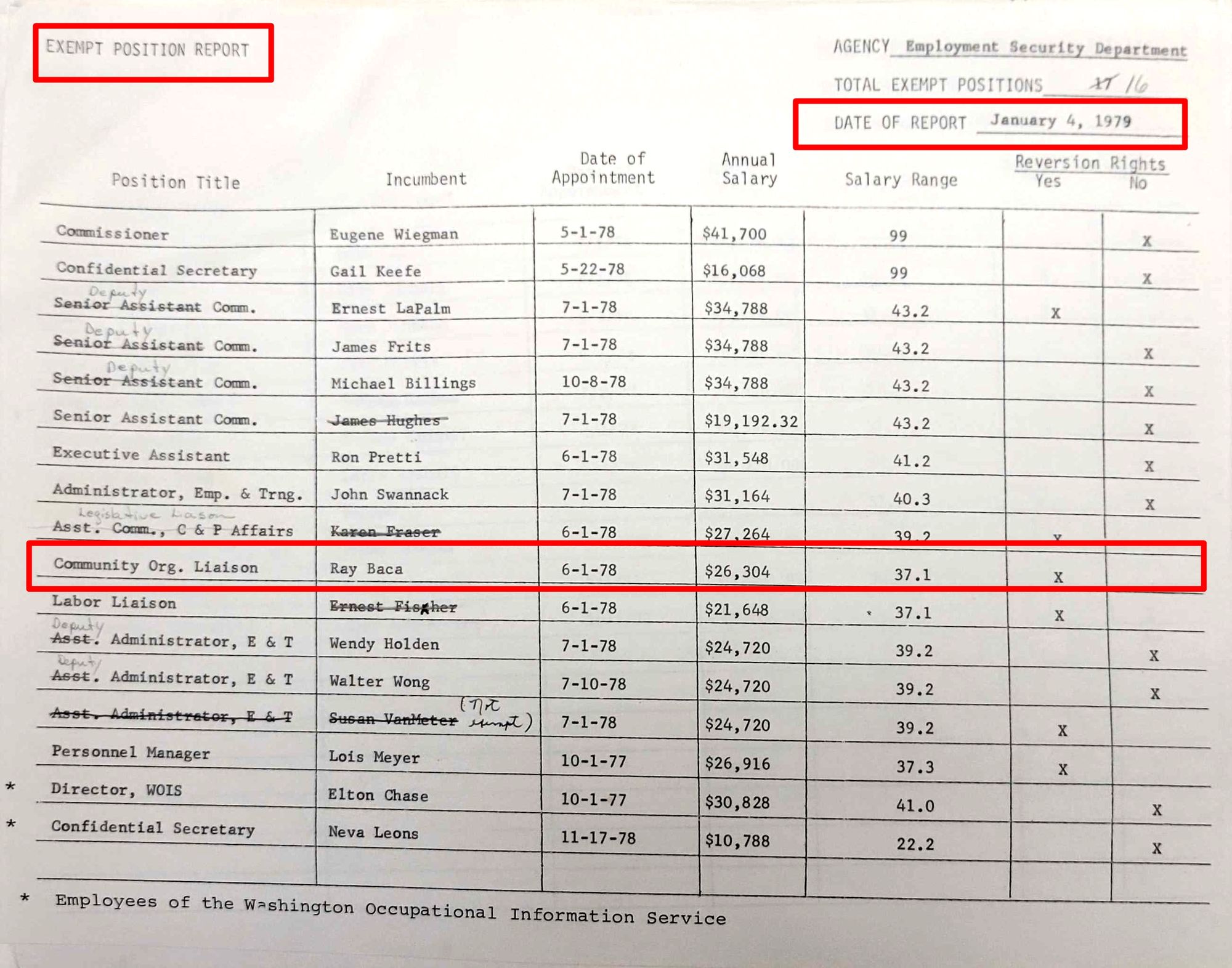

The Hoover Institute Library and Archives archivists found a roster dated January 4, 1979, listing the “exempt” employees in the Employment Security Department. On the roster, a total of 16 titled jobs were deemed “exempt.” Ray Baca was listed as “Community Org. Liaison,” consistent with the Tacoma News Tribune article of the previous June. I have embedded an image of that document below.

Under Washington State law, an “exempt” employee is one hired outside of normal civil service procedures. This can be done for various reasons, including designation by the governor or various agency heads that certain positions should be filled on an “exempt” basis for various reasons. One of the recommendations of the "Mexican American Ad Hoc Committee” in its May 25, 1977 memo had been that the Ray Administration use this authority to place more Hispanics throughout the state government. It seems likely that Baca’s promotion here was executed in this way, in recognition of his political support for Governor Ray.

The position that Baca was awarded, although deemed “senior” by the newspaper, in salary ranked 10th among the 16 “exempt” positions in this fairly obscure state agency.

On page 67 of his 2011 book Born on the Edge of Ground Zero, Baca summarized his activities during Ray’s term as governor. I reproduce that paragraph in total.

I went to work for Governor Ray in Olympia, the State Capitol [sic] of Washington, where I traveled throughout the state, visiting each of the thirty-nine Counties, enhancing my knowledge of the demographics of each County, working very closely with local, federal and state officials, advising the Governor on various issues, and serving as liaison to community organizations in the development and coordination of Governor Ray’s Town Hall Meetings. I attended various functions representing her office, when Governor wasn’t able to attend. (p. 67)

This paragraph, if taken alone, was probably not wildly far from the truth, although the language was puffed up. It appears that Baca may have served as de facto low-level political operative– on the payroll of an obscure state agency, performing certain “community outreach” services on state time, and likely doing double duty as a grassroots political glad-hander for the Ray Administration.

What is described in Baca’s own paragraph, and what we see in the documents posted above, is a very long ways from “the governor’s executive staff,” and far removed from the sort of position that a true “kingmaker” would have warranted.

PLAGARISM AND IDENTITY THEFT BY RAY BACA IN SUPPORT OF HIS BOGUS CLAIMS TO BE A CLOSE ASSOCIATE OF DIXY LEE RAY

If Reme Baca, in 2011 book, Born on the Edge of Ground Zero, had contented himself with the one paragraph on page 67 that I have quoted above, I would end this article here. Unfortunately, Baca’s book contains nine pages (pp. 60-69) pertaining to his purported close association with Dixy Lee Ray. Careful scrutiny of those pages deals a further blow to Baca’s credibility.

Baca begins the section by saying, “I played a substantial role in the development and coordination of the Hispanic vote in the state wide primary and general elections [in 1976].” The term “substantial” is elastic enough that I would not quarrel with the words of that single sentence.

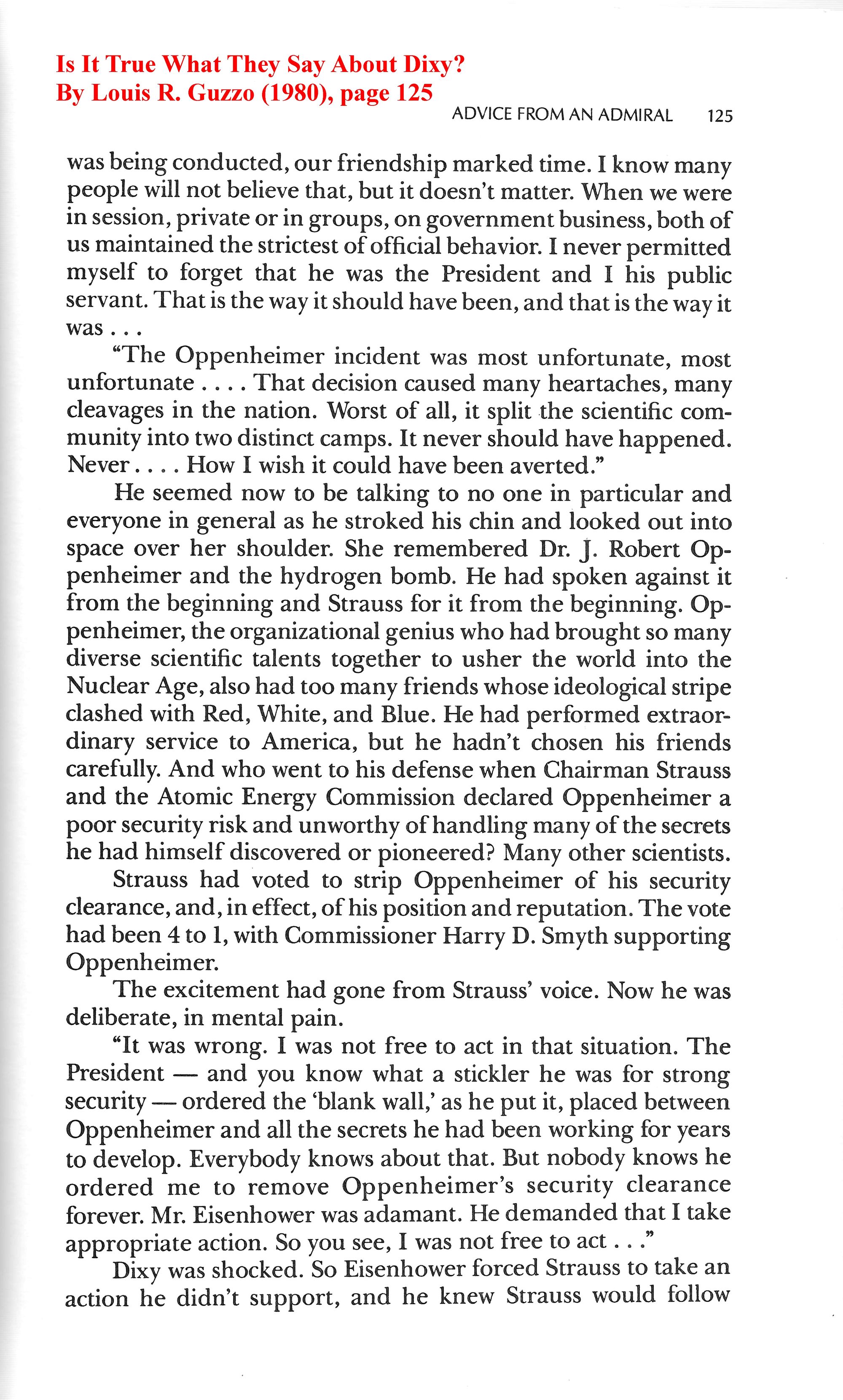

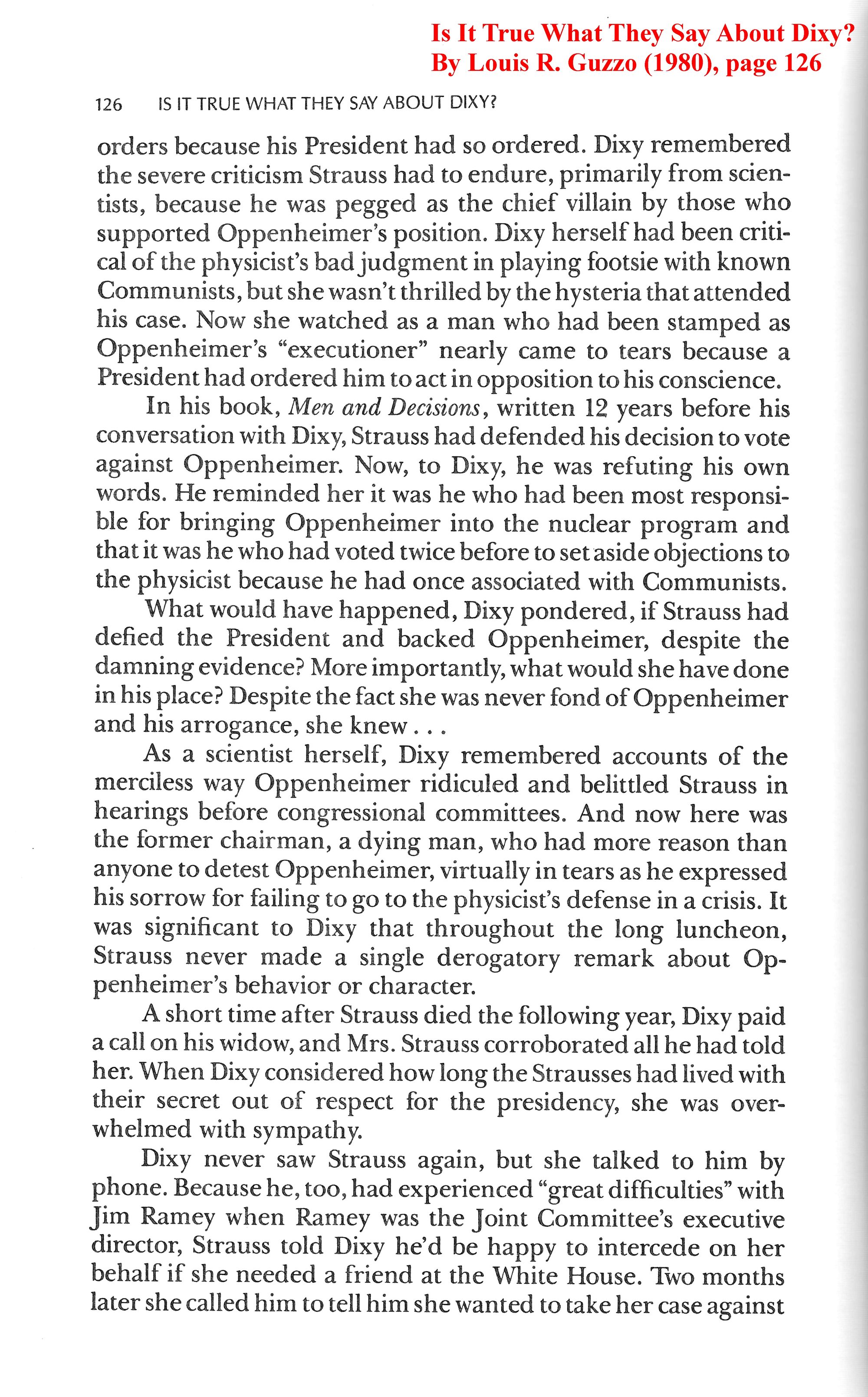

However, what immediately followed that statement in the book are over six pages of detailed information about experiences that Dixy Lee Ray had when she was on the Atomic Energy Commission, including an involved “inside story” relating to J. Robert Oppenheimer. Baca presented this material seamlessly and without attribution, in a way that could only lead the reader to believe that Baca was relaying information that he had heard directly from Dixy Lee Ray or from her close associates.

In reality, however, the approximately six pages of that material was lifted virtually verbatim, without attribution, from a biography of Ray that written by Louis R. Guzzo, who was perhaps Dixy Lee Ray’s closest professional associate during this entire era.

Guzzo had served ten years as managing editor and then executive editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, known for pushing aggressive investigative reporting uncovering political corruption and cronyism. He was also “a friend to Dr. Dixy Lee Ray for close to 20 years.” In 1975 Guzzo resigned from the newspaper to became Ray’s public affairs director at the State Department. During her 1976 campaign his title was “press director,” and on her executive staff he was “counselor to the governor.”

Guzzo’s admiring biography, Is It True What They Say About Dixy?, was published in early 1980, as Ray entered an election season in which she was ultimately defeated in the Democratic primary in September, 1980. The book contained innumerable anecdotes and observations gleaned from his close daily association with Ray. Baca simply lifted this material and dropped it seamlessly into his narrative, to make it appear that was Baca who was privy to Ray’s private thoughts about people, policies, and incidents. Here again, as I found elsewhere – for example, with respect to Officer Eddie Apodaca -- Baca used real people as characters in his works of fantasy.

Baca did list Guzzo’s book on an inconspicuous “bibliography” that appeared on the last page of Baca’s book. Perhaps Baca thought that putting the book on the list gave him sufficient cover, if anyone happened to notice that he had pasted six pages of Guzzo’s words into his narrative. In reality, Baca’s appropriation of Guzzo’s material was pure and brazen plagiarism.

(Many other pages of Baca’s 2011 book were also obviously cut and pasted from other sources, sometimes in a not-very-adroit manner. I do not bother to enumerate these here, because those thefts dealt primarily with matters not pertinent to Baca's UFO crash narratives.)

On the left (or above, depending on your device), pages from Reme Baca's 2011 book Born on the Edge of Ground Zero. On the right or below, the source text as found in Is It True What They Say About Dixy?, a 1980 book by Louis R. Guzzo, a close associate of Dixy Lee Ray.

THE DEFEAT OF GOVERNOR RAY, THE BACAS’ 1994 UFO SIGHTING, BACA’S MOVE TO CALIFORNIA IN 1995, AND BACA’S “MUFON PERIOD”

Ray served only a single term as governor (January 12, 1977 to January 14, 1981). As detailed in Guzzo’s 1980 book and in other sources, Governor Ray took many actions that alienated many previous supporters, including the political strategist, Blair Butterworth, who had been credited with her 1976 upset primary victory. Butterworth jumped ship and ran the successful campaign of James McDermott, who defeated Ray in the Democratic primary when she sought renomination in 1980. (McDermott got 33%, Lee only 29% in Washington State’s “all party” primary.)

The 2005 Baca vita stated:

Reme served on Ray's Executive staff, and when the Governor was defeated in her bid for re-election, Reme became an Insurance Agent, after which he was appointed to Tacoma Housing Authority by Mayor Doug Sutherland, where he served as Chairperson. He then moved to California and became an independent Insurance Broker, with offices in Oxnard, Santa Paula and Santa Barbara, where he became a member of MUFON, and met Dr. Roger Leir, who was then the chairman of the Ventura Chapter.

In his 2011 book, Baca recites a few low-level political activities following Ray’s defeat, a stint in “the plywood industry,” and then his transition into insurance sales.

Suffice to say that what was described by Baca himself in those two sources is far removed from the career path that one generally might expect to see from someone who had actually been responsible for the election of a governor, and/or who had served on a governor’s executive staff.

Baca later said that before moving to California, which occurred in July 1995, he and his wife experienced an impressive UFO sighting over Takoma one Sunday evening in July 1994—an event that made a UFO believer out of Virginia (Jeannie) Baca, who previously rejected the notion of extraterrestrial visitation. I discuss the 1994 sighting in detail in Crash Story File: The Baca UFO Sighting of July 1994.

In a 2010 interview, Baca said that he and his family lived in California for seven years (July 1995-2002). I found records of Baca’s registration as an insurance agent in California, for four different types of insurance. His last licenses for accident and health and life-only insurance expired May 31, 1998. His last licenses as casualty broker-agent and property broker-agent expired May 31, 2002.

I do not know how well acquainted Reme Baca was with Dr. Roger Leir, who died in 2014, but Baca did mention the association in the 2005 Baca vita. Dr. Leir (1935-2014) was a fairly high-profile figure in the some ufological circles at the time. Leir was a podiatric surgeon who removed metallic objects from the bodies of many persons, objects that he came to believe were devices implanted by aliens. Leir wrote three UFO-oriented books, including The Aliens and the Scalpel (1999) and Casebook: Alien Implants (2000). He was a featured speaker at various UFO conferences of the era.

I found it a bit intriguing that in 2003, Leir went to Varginha, Brazil, to investigate a report of a crashed UFO, in association with which the recovery of live aliens occurred, according to some accounts. It was also in 2003 that the Baca-Padilla tale of a UFO crash involving live aliens was first published.

Generally, however, I have so far not been very successful in learning much about Baca’s years of involvement with MUFON in California. I would welcome contacts from readers who could shed more light on this period of Baca’s odyssey (at douglas.dean.johnson // at // gmail // dot // com.

One reported incident of interest came to my attention. In a copyrighted essay published in 2021, titled “The Passport to Magonia Ends at Trinity,” Donald R. Schmitt, author of many UFO-related books, wrote:

It was in the late summer of 1997 [later corrected to 1995; see below] that I had just completed a Roswell presentation in Ventura, California, just north of Los Angeles. I was introduced to a man who described that he was witness to the crash in 1947 but added that it was on “The Plains,” which I assumed to be the Plains of San Agustin... I did take down his name [Reme Baca] and contact information and stored it in my witness-lead folder....It was abundantly clear that he became immersed in the subject, read books about the Roswell Incident, and attended my lecture on the subject when we were introduced. He even had me sign a copy of a Roswell book. [UPDATE: In late May, 2023, Donald Schmitt told me that after further review of his records, he concluded that his conversation with Reme Baca occurred following a summer, 1995 lecture in Ventura County, California (rather than summer, 1997, as he had originally recalled).]

Sometime around 2001, Baca underwent open-heart surgery. Baca retired back to the Tacoma area (Gig Harbor, a suburb of Takoma) in or about 2002. He soon reconnected with his childhood friend, Joseph Lopez (Jose) Padilla.

[UPDATE: During 2002, and perhaps into early 2003, Baca pitched an account of a childhood UFO-crash adventure by Baca and Jose Padilla to several people associated with producing Roswell-themed TV productions and books. In late 2002 or early 2003, UFO writer Tom Carey recorded a 30-minute interview in which Baca made his pitch. The story told by Baca on that recording was set in a different year (1946), and differed in nearly every other salient aspect, from the Baca-Padilla 1945 UFO-crash tale that was first published in October-November, 2003, and later carried to a wide audience by Jacques Vallee and Paola Harris. Documentation of this damning evidence of Baca's proclivity for presenting fiction as fact (including the unedited audio file) is set forth in my article The Reme Baca Smoking-Gun Interview (May 20, 2023).]

Baca died on June 18, 2013. But his last tall tale lives on.

REVISIONS SINCE ORIGINAL PUBLICATION OF THIS ARTICLE ON MAY 1, 2023

(1) September 26, 2023: I added a paragraph near the end regarding my discovery of a recording in which Reme Baca pitched an entirely different boyhood UFO-crash "memory" to UFO writer Tom Carey, less than a year before the first publication of the story on which Trinity: The Best-Kept Secret is based.

(2) September 26, 2023: I added a note that Donald Schmitt, after review of his files, believes that his conversation with Reme Baca occurred after a lecture that Schmitt gave in Ventura County, California, in 1995, not 1997.